Emily Brontë was born July 30, 1818, in Thornton, Yorkshire, the fifth of Patrick and Maria Bronte’s six children. Within a few years, the family moved to the West Yorkshire village of Haworth, where Patrick was the curate (priest) of the parish church. Bronte lived nearly her entire life at Haworth Parsonage. Within that small household, the family dealt with such troubles as sickness, poverty, brutality, alcoholism, and death. Their mother died of cancer not long after the birth of her youngest daughter, Anne, when Emily Brontë was only three. When Emily was six, she and her three older sisters, Maria, Elizabeth, and Charlotte, were sent to the Clergy Daughter’s School at Cowan Bridge. Maria and Elizabeth contracted tuberculosis at the school and died soon afterward; Emily and Charlotte were subsequently withdrawn. With each successive blow, the family grew closer, shutting out the world around them and taking comfort from those who remained—even if those people were the source of the trouble, like their brother Bramwell, who suffered from alcoholism. All six of the Brontë children died before the age of 40.

Emily Brontë was born July 30, 1818, in Thornton, Yorkshire, the fifth of Patrick and Maria Bronte’s six children. Within a few years, the family moved to the West Yorkshire village of Haworth, where Patrick was the curate (priest) of the parish church. Bronte lived nearly her entire life at Haworth Parsonage. Within that small household, the family dealt with such troubles as sickness, poverty, brutality, alcoholism, and death. Their mother died of cancer not long after the birth of her youngest daughter, Anne, when Emily Brontë was only three. When Emily was six, she and her three older sisters, Maria, Elizabeth, and Charlotte, were sent to the Clergy Daughter’s School at Cowan Bridge. Maria and Elizabeth contracted tuberculosis at the school and died soon afterward; Emily and Charlotte were subsequently withdrawn. With each successive blow, the family grew closer, shutting out the world around them and taking comfort from those who remained—even if those people were the source of the trouble, like their brother Bramwell, who suffered from alcoholism. All six of the Brontë children died before the age of 40.

Brontë’s life was insular. She had a patchwork of formal education from Cowan Bridge, the Roe Head School in Mirfield, and a stint at the Pensionnat Heger, supplemented by a variety of lessons given by people in the Haworth community and intensive reading and study at home. Patrick Brontë had an extensive library, and along with scripture, all the siblings were encouraged to read as much as possible from classical authors such as Homer, Virgil, and Shakespeare, neoclassical writers Bunyan, Milton, Pope, Jonson, Gibbon, and Cowper, and more contemporary romantic poets and authors such as Burns, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Scott, Southey, and Byron. Emily and her surviving sisters, the novelists Charlotte Brontë (Jane Eyre) and Anne Brontë (Agnes Grey), created the imaginary kingdoms of Angria and Gondal when they were children, and these imaginative worlds eventually spilled over into their real one.

Brontë’s life was insular. She had a patchwork of formal education from Cowan Bridge, the Roe Head School in Mirfield, and a stint at the Pensionnat Heger, supplemented by a variety of lessons given by people in the Haworth community and intensive reading and study at home. Patrick Brontë had an extensive library, and along with scripture, all the siblings were encouraged to read as much as possible from classical authors such as Homer, Virgil, and Shakespeare, neoclassical writers Bunyan, Milton, Pope, Jonson, Gibbon, and Cowper, and more contemporary romantic poets and authors such as Burns, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Scott, Southey, and Byron. Emily and her surviving sisters, the novelists Charlotte Brontë (Jane Eyre) and Anne Brontë (Agnes Grey), created the imaginary kingdoms of Angria and Gondal when they were children, and these imaginative worlds eventually spilled over into their real one.

The sisters’ first published work, a book of poetry submitted under the male pseudonyms Currer (Charlotte), Acton (Anne), and Ellis (Emily) Bell, sold only two copies. The volume contained eighteen poems authored by Emily. Of them, one reviewer complimented her “fine quaint spirit” and asserted that she had “things to speak that men will be glad to hear,—and an evident power of wing that may reach heights not here attempted.” The siblings were unusually close, lending each other critique and encouragement. The painting here of the Brontë sisters was created by their brother Bramwell; Anne sits to the left, Emily in the center, and Charlotte on the right. Bramwell originally included himself but painted out his image later, as you can see from the restoration.

All three sisters wrote fiction in addition to poetry. They submitted their respective novels under their Bell pseudonyms in a single envelope; if the submission was returned by a publisher, Charlotte would cross out that name, add a new address to the bottom, and send it out again. In 1847, Charlotte’s Jane Eyre was published to instant acclaim (Queen Victoria was a fan), becoming a bestseller. Anne’s Agnes Grey was released by a different publisher, outshone by her sister’s work. In early 1848, Emily’s novel and Anne’s second, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, were accepted and published as a set. Anne’s single volume was a sensation and sold out. Emily’s novel, Wuthering Heights, did not fare as well. Intense and passionate and peopled with characters who neither sought nor deserved redemption, as was expected by those in Victorian times, the work unsettled readers and reviewers alike.

When Brontë died, several reviews of Wuthering Heights were found in her desk. As you can see from these snippets, there is no common agreement about the work to be found:

When Brontë died, several reviews of Wuthering Heights were found in her desk. As you can see from these snippets, there is no common agreement about the work to be found:

Anonymous reviewer, Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper, 15 January 1848

“Wuthering Heights is a strange sort of book,—baffling all regular criticism; yet, it is impossible to begin and not finish it; and quite as impossible to lay it aside afterwards and say nothing about it.”

Unknown reviewer from an unknown publication, about 1847:

“This is a work of great ability, and contains many chapters, to the production of which talent of no common order has contributed.”

Anonymous reviewer for the Examiner, 8 January 1848:

“This is a strange book. It is not without evidences of considerable power: but, as a whole, it is wild, confused, disjointed, and improbable; and the people who make up the drama, which is tragic enough in its consequences, are savages ruder than those who lived before the days of Homer.”

Paterson’s magazine (U.S.)

“Read Jane Eyre… but burn Wuthering Heights.”

The Penguin Classics Reader’s Guide to Wuthering Heights suggests that “This strong reaction was due in part to the book’s intense examination of the human spirit. Readers accustomed to novels such as those by Jane Austen, published thirty-five years before, sought a realistic portrayal of the mores and manners of the English upper classes. Wuthering Heights, in contrast, focused not on society, but on the minds, hearts, and souls of its members.”

In a sense, Emily Brontë is very much like the American poet Emily Dickinson. Both led secluded lives, but their seclusion masked an uncommon knowledge of human nature and the passions and questions that control it. Neither woman married, and there is much speculation about the nature of any relationships they might have had outside of their respective families. Each left behind a fixed body of work. In Dickinson’s case, none of her poems were published until after her death. Brontë lived to see one book of poetry and Wuthering Heights published, with another novel contracted by the same publisher. After Emily’s death, her sister Charlotte gathered and published more of Emily’s poems, including “Stanzas” below. The themes and passions in her poetry mirror those in her great novel, allowing us a glimpse of a woman whose imaginative inner life belied her secluded reality.

Stanzas

Often rebuked, yet always back returning

To those first feelings that were born with me,

And leaving busy chase of wealth and learning

For idle dreams of things that cannot be:

To-day, I will seek not the shadowy region;

Its unsustaining vastness waxes drear;

And visions rising, legion after legion,

Bring the unreal world too strangely near.

I’ll walk, but not in old heroic traces,

And not in paths of high morality,

And not among the half-distinguished faces,

The clouded forms of long-past history.

I’ll walk where my own nature would be leading:

It vexes me to choose another guide:

Where the gray flocks in ferny glens are feeding;

Where the wild wind blows on the mountain side.

What have those lonely mountains worth revealing?

More glory and more grief than I can tell:

The earth that wakes one human heart to feeling

Can centre both the worlds of Heaven and Hell.

The year Wuthering Heights was published, Emily fell ill, complaining of difficulty breathing and pains in her chest. It was tuberculosis. Bramwell had also contracted the disease. He succumbed in September of 1848. Emily died December 19, 1848, at the age of 30. Anne followed the next May. Charlotte, the lone surviving Brontë sibling, continued to write and publish her own work in addition to serving as editor for subsequent editions of her sisters’ work. She married her father’s curate Arthur Nicholls in 1854 and is said to have lived a happy life until her own death from tuberculosis in 1855. Their father Patrick outlived them all, dying in 1861.

Sources:

http://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/reviews.htm

http://www.biography.com/people/emily-bronte-9227381

http://www.haworth-village.org.uk/brontes/emily/emily.asp

http://www.poetry-archive.com/b/stanza.html

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/emily-bronte

http://www.penguinclassics.co.uk/nf/shared/WebDisplay/0,,82350_1_10,00.html

When Brontë died, several reviews of Wuthering Heights were found in her desk. As you can see from these snippets, there is no common agreement about the work to be found:

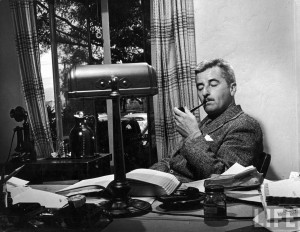

When Brontë died, several reviews of Wuthering Heights were found in her desk. As you can see from these snippets, there is no common agreement about the work to be found: Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Poetry Focus: Singing America

Langston Hughes’ 1925 poem “I, Too, Sing America” is one of the best-known of all poems of the Harlem Renaissance. Its message of inclusive hope reverberated across the twentieth century and continues to be a touchstone for people seeking a place at the table. Here are several interpretations of the poem to consider as you review the text.

First, Langston Hughes reading his own poem:

The political advocacy group Emerging US made the poem the focal point for this video focusing on the Mexican-American experience in Los Angeles:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Z2r721Vzls#action=share

YouTube user IndianaTheGreat juxtaposed images from the Civil Rights Era to audio of Denzel Washington reading the poem in the film The Great Debaters and clips from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington.

Hughes’s poem was written as a response to Walt Whitman’s famous free-verse poem “I Hear America Singing.” This visual representation of the poem by YouTube user Dustin Rowland illustrates the breadth of the American experience Whitman intended to celebrate.

Finally, this is Whitman himself, reading his poem “America.”

Comments Off on Poetry Focus: Singing America

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, authors, commentary, poetry