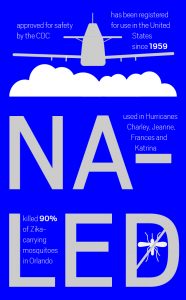

After failed use of common chemicals, Miami officials decided to use naled, a strong but highly controversial insecticide, to attempt to kill mosquitoes carrying the Zika virus.

As the Zika virus spreads and concern follows suit, researchers look for a way to kill mosquitoes carrying it. The insecticide naled is the best breakthrough so far.

According to the Extension Toxicology Network, naled works as a quick, non-systematic contact and stomach poison in insects and mites. Generally, farmers or greenhouse workers use it to kill agricultural bugs. Veterinatrians sometimes use it to kill parasitic worms in dogs. Most recently, naled became popular because it can rapidly kill mosquitoes carrying the Zika virus.

CBS News correspondent David Begnaud reports that more commonly used chemicals, such as pyrethroids, are not very effective. In result, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention find controlling the virus’ spread difficult. This issue is most prominent in Miami neighborhood Wynwood. As of Aug. 2, Wynwood reports 14 locally transmitted cases of Zika virus.

County officials turned to another option: naled. They sent a plane carrying the insecticide released the spray over Miami Beach and Wynwood. The New York Times reports that, as of Sept. 2, naled succeeded in killing at least 90 percent of the targeted mosquitoes. Evidently, naled proves its superiority in efficiency over the alternative chemicals that protestors favor; use of such products is counterproductive in the fight against the Zika virus.

However, some residents worry that naled has too great a potential risk, noting that the pesticide was banned in Europe in 2012. Naled does indeed have some risk. The European Union classifies naled as harmful to aquatic life, and dangerous if swallowed or if it comes in contact with skin. If used in high concentrations, naled can cause nausea, dizziness, confusion, convulsions and death in humans. Understandably, such possibilities may lead to concern for those exposed to it.

But the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency informs that if public health mosquito control programs use naled in accordance to label instructions, the insecticide will not pose a risk to people. The CDC seconds this, reporting that the drastic aforementioned effects would require higher concentrations than licensed professionals dispense during spraying. Therefore, people should refrain from fretting over such false health concerns.

With the CDC and EPA debunking the fear of human harm, environmental effects become the more pressing issue. Addressing the issue, the ETN reports several environmental fate studies demonstrate that naled degrades rapidly under typical environmental conditions. Concern, however, may prevail for naled’s moderate toxicity to birds, toxicity to most aquatic life, and high toxicity to bees. Notwithstanding, the Zika virus is too problematic for these limited environmental concerns.

Instead, the biggest distress should lie with pregnant women. Their exposure to the virus can lead to a birth defect of unusually small heads known as microcephaly that can result in developmental problems, and other severe brain abnormalities in babies, according to the CDC and the World Health Organization. The organization also concluded that an infection may trigger Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare neurological disorder that can result in paralysis.

Already, at least 58 countries have reported active Zika outbreaks, including the United States, according to the New York Times. And most alarmingly, there is currently no available treatment for the virus. Although companies and scientists work to develop a safe vaccine, none expect it to be ready until two or three years.

So despite any environmental concern for the use of naked, people should focus more on the concern for the spread of Zika and its growing effect on others; naled offers more help than harm to those exposed to it.

To see the opposite point of view, click here.