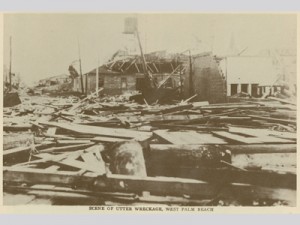

The central historical event of Their Eyes Were Watching God is the Great Okeechobee Hurricane of 1928. The hurricane had already wreaked havoc across the Caribbean, most notably on the Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Bahamas. The storm made landfall in South Florida on September 17 in Palm Beach County. The internal pressure of the storm was 929 millibars, with wind speeds of around 145 mph, ranking it sixth on the list of most intense storms to hit the United States. Only four storms have made landfall in Florida with higher wind speeds: the unnamed hurricane of 1919, the Labor Day hurricane of 1935, Hurricane Andrew in 1992 and Charley in 2004. The Saffir-Simpson scale that divides hurricanes into categories had not yet been invented, but based on these measurements, the Great Okeechobee hurricane would have made landfall in Florida at Category 4.

Although the storm caused a great deal of property damage in Palm Beach and other coastal areas, the real devastation happened as the storm moved inland over Lake Okeechobee (Okeechobee is a Seminole word for “big water”). Strong rains in the weeks before the storm had raised the water level in the lake. Storm winds drove water to the south end of the lake, and in two locations, the levee surrounding the lake broke.

Although the storm caused a great deal of property damage in Palm Beach and other coastal areas, the real devastation happened as the storm moved inland over Lake Okeechobee (Okeechobee is a Seminole word for “big water”). Strong rains in the weeks before the storm had raised the water level in the lake. Storm winds drove water to the south end of the lake, and in two locations, the levee surrounding the lake broke.

In his book Okeechobee Hurricane, Lawrence E. Will described the flood this way:

The period of the lull here had apparently been between 8:30 and 9:30 that night. The exact time of the breaking of the dike is difficult to determine. There were several breaks and they may have occurred at slightly different times. Although it took an appreciable time for the flood to arrive in Belle Glade, those in the hotel said that when it did arrive, it rose on the steps at the rate of an inch a minute. The highest crest, which was during the maximum velocity of the wind during the second phase of the storm, was, according to my recollection, at 10:20 PM. This crest was a rolling swell of short duration, after which the water fell about a foot and remained nearly constant for twenty minutes. This mark in Belle Glade was about seven feet above the ground, nearer the lake it was a great deal higher, for example, in Stein’s house at Chosen, 11 feet 3 inches, and on Torry (Island) 11 feet, 8 inches, and similar heights in South Bay. As the flood advanced, it necessarily fanned out, becoming shallower. At the (University of Florida) Experiment Station its maximum depth was three feet, and that, strangely enough, according to foreman Tedder, was after daylight.

As the category 4 hurricane moved inland, the strong winds piled the water up at the south end of the lake, ultimately topping the levee and rushing out onto the fertile land. The storm surge alone was nearly ten feet. The floodwaters in Belle Glade, on the southern shore of the lake, rose at a rate of one inch per minute and nearly topped seven feet. Thousands of people, mostly non-white migrant farm workers, drowned as water several feet deep spread over an area approximately 6 miles deep and 75 miles long around the south end of the lake.

As the category 4 hurricane moved inland, the strong winds piled the water up at the south end of the lake, ultimately topping the levee and rushing out onto the fertile land. The storm surge alone was nearly ten feet. The floodwaters in Belle Glade, on the southern shore of the lake, rose at a rate of one inch per minute and nearly topped seven feet. Thousands of people, mostly non-white migrant farm workers, drowned as water several feet deep spread over an area approximately 6 miles deep and 75 miles long around the south end of the lake.

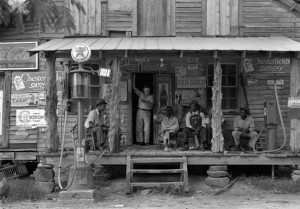

The initial death toll set by the Red Cross was just under 2,000 people. However, that number most likely minimized the actual loss of life in order to prevent a negative effect on tourism to the state. The fact that most of the dead were migrant workers also played a part. The National Weather Service set the official death toll at more than 2,500* in 2003. The asterisk exists because the true death toll is unknown. Many of the bodies of the migrant workers were washed into the Everglades and never recovered. This storm was the second most devastating in terms of loss of life in U.S. history, ranking behind the Galveston Hurricane of 1900.

The burial scenes depicted in Their Eyes Were Watching God illustrate the difficulty in dealing with the huge loss of life, animal and human, and the necessity of burying so many in the short time required by Florida’s heat and humidity. They also call into attention the additional effect that segregation had on the tragedy. Whites were buried first, as many in private graves as possible until the heat demanded other measures. Blacks were more likely to have been interred in mass graves. Separate memorial services were held for white and black victims. Markers commemorating the mass burials may be found in West Palm Beach, one at Woodlawn Cemetery, where nearly 70 whites were buried, and another close to the intersection of 25th Street and Tamarind Avenue which marks the resting place of nearly 700 blacks. This marker is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Liz Doup’s story in the Broward Sun-Sentinel discusses the human cost of the hurricane, including interviews from survivors. Read the story here.

Information from:

Hurricanes: Science and Society, http://www.hurricanescience.org/history/storms/1920s/Okeechobee/

Memorial Page for the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane, http://www.srh.noaa.gov/mfl/?n=okeechobee