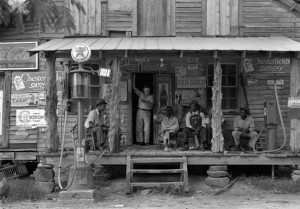

Their Eyes Were Watching God begins with Janie’s return to Eatonville, told primarily through the onlookers gathered on the porch in front of Joe Starks’s store: “It was the time for sitting on porches beside the road. It was the time to hear things and talk. These sitters had been tongueless, earless, eyeless conveniences all day long. Mules and other brutes had occupied their skins. But now, the sun and the bossman were gone, so the skins felt powerful and human. They became lords of sounds and lesser things. They passed nations through their mouths. They sat in judgment.”

Throughout the Eatonville section of the novel, the porch serves as the center of town life. It’s the place to go for a game of checkers or a cold drink on a hot day, the one place you want to be to hear the news, swap stories, “play the dozens,” and gossip. “When the people sat around on the porch and passed around the pictures of their thoughts for the others to look at and see, it was nice.” (Chapter 6)

Janie realizes the importance of the porch as a way to integrate fully into the life of the town. Jody’s determination to keep her in the store reinforces his belief of her as something better than the rest of the townswomen, the “bell cow” whose prominence complements his own.

Porches serve as a touchstone in much of Hurston’s work, like her story “Sweat” and her novel Seraph on the Suwanee. In her autobiography Dust Tracks on A Road, Hurston recounted her early experiences in Eatonville:

“I know that Joe Clarke’s store was the heart and spring of the town. Men sat around the store on boxes and benches and passed this world and the next one through their mouths. The right and the wrong, the who, when and why was passed on, and nobody doubted the conclusions…For me, the store porch was the most interesting place that I could think of. I was not allowed to sit around there, naturally. But, I could and did drag my feet going in and out whenever I was sent there…But what I really loved to hear was the menfollks holding a “lying” session. That is, straining against each other in telling folktales. God, Devil, Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Sis Cat, Brer Bear, Lion, Tiger, Buzzard, and all the wood folk walked and talked like natural men.”

As a cultural anthropologist, Hurston certainly knew the connections between the stories and folktales she heard on those porches and those of West Africa. Trickster tales of Anansi the Spider migrated across the Middle Passage and found new homes in the American South, Anansi becoming the fabled trickster Brer Rabbit (and his Brooklyn-accented descendant, Bugs Bunny) and the porch taking the place of the talking stool reserved for the tribal chief.

The Act I Setting of Mule Bone, written in 1930 by Langston Hughes and Hurston from her story “A Bone of Contention,” describes how the porch should look.

SETTING: The raised porch of JOE CLARKE’s Store and the street in front. Porch stretches almost completely across the stage, with a plank bench at either end. At the center of the porch three steps leading from street. Rear of porch, center, door to store. On either side are single windows on which signs, at left, “POST OFFICE,” and at right, “GENERAL STORE” are painted. Soap boxes, axe handles, small kegs, etc., on porch on which townspeople sit and lounge during action. Above the roof of the porch the “false front,” or imitation second story of the shop, is seen with large sign painted across it “JOE CLARKE’S GENERAL STORE.” Large kerosene street lamp on post at right in front of the porch.

Saturday afternoon and the villagers are gathered around the store. Several men sitting on boxes at edge of porch chewing sugar cane, spitting tobacco juice, arguing, some whittling, others eating peanuts. During the act the women all dressed up in starched dresses parade in and out of store. People buying groceries, kids playing in the street, etc. General noise of conversation, laughter and children shouting. But when the curtain rises there is a momentary lull for cane-chewing. At left of porch four men are playing cards on a soap box, and seated on the edge of the porch at extreme right two children are engaged in a checker game, with the board on the floor between them.

Mule Bone was based on an African-American folktale. The play was intended to be the first of what Hurston hoped would be a truly “black vernacular” theater; however, a falling out between the authors prevented the play from ever being produced in their lifetimes. A production of Mule Bone finally made its debut in 1991. The fascinating story behind the conflict may be found here.

Mule Bone was based on an African-American folktale. The play was intended to be the first of what Hurston hoped would be a truly “black vernacular” theater; however, a falling out between the authors prevented the play from ever being produced in their lifetimes. A production of Mule Bone finally made its debut in 1991. The fascinating story behind the conflict may be found here.

“Lord of the Flies is a very serious book which has to be introduced seriously. The danger of such an introduction is that it may suggest that the book is stodgy. It is not. It is written with taste and liveliness, the talk is natural, the descriptions of scenery enchanting. It is certainly not a comforting book. But it may help a few grownups to be less complacent and more compassionate, to support Ralph, to respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart. At the present moment (if I may speak personally), it is respect for Piggythat seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders.”

“Lord of the Flies is a very serious book which has to be introduced seriously. The danger of such an introduction is that it may suggest that the book is stodgy. It is not. It is written with taste and liveliness, the talk is natural, the descriptions of scenery enchanting. It is certainly not a comforting book. But it may help a few grownups to be less complacent and more compassionate, to support Ralph, to respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart. At the present moment (if I may speak personally), it is respect for Piggythat seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders.” “The South-Sea island setting suggests everyone’s fantasy of lotus-eating escape or refuge from troubles and care. But for Golding this is the sheerest fantasy: there is no escape from the agony of being human, no possibility of erecting utopian political systems where all will go well. Man’s inescapable depravity makes sure “it’s no-go” on Golding’s island just as it does on the various islands visited by Gulliver in Swift’s excoriating examination of the realities of the human condition.”

“The South-Sea island setting suggests everyone’s fantasy of lotus-eating escape or refuge from troubles and care. But for Golding this is the sheerest fantasy: there is no escape from the agony of being human, no possibility of erecting utopian political systems where all will go well. Man’s inescapable depravity makes sure “it’s no-go” on Golding’s island just as it does on the various islands visited by Gulliver in Swift’s excoriating examination of the realities of the human condition.”

Daniel Defoe’s 1719 tale Robinson Crusoe exemplifies many of the hallmarks of these tales we find familiar: a stranded hero, a deserted island, meetings and clashes with various native cultures, and eventual rescue, where the hero returns home a changed man for his experience. The book’s popularity spawned an entire subgenre of literature called Robinsonade, all of which contain a stranded hero, a new beginning, encounters with natives, and commentary on society. These influences can be seen in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a particularly biting piece of satire that uses the castaway motif to savage various aspects of English society, and the modern film Cast Away (2000),

Daniel Defoe’s 1719 tale Robinson Crusoe exemplifies many of the hallmarks of these tales we find familiar: a stranded hero, a deserted island, meetings and clashes with various native cultures, and eventual rescue, where the hero returns home a changed man for his experience. The book’s popularity spawned an entire subgenre of literature called Robinsonade, all of which contain a stranded hero, a new beginning, encounters with natives, and commentary on society. These influences can be seen in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a particularly biting piece of satire that uses the castaway motif to savage various aspects of English society, and the modern film Cast Away (2000),  in which Tom Hanks plays a stranded Federal Express executive who survives alone on an island in the South Pacific for four years with the help of the contents of FedEx packages that washed up on the island with him, including a personified volleyball named Wilson.

in which Tom Hanks plays a stranded Federal Express executive who survives alone on an island in the South Pacific for four years with the help of the contents of FedEx packages that washed up on the island with him, including a personified volleyball named Wilson. Part of The Coral Island‘s popularity was its clear messages about morality and choices. Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin of the story are tested by their isolation, their encounters with pirates, and their interactions with the cannibalistic inhabitants of nearby islands. Through a series of adventures, the boys’ friendship and loyalty are tested and proved, and at the end the three friends, older and wiser, sail back to England together. Ballantyne included them in a sequel, The Gorilla Hunters, in 1861.

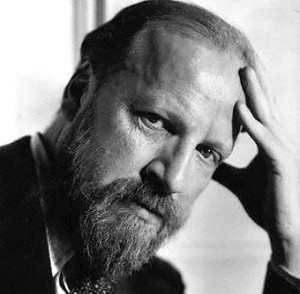

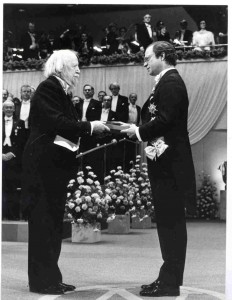

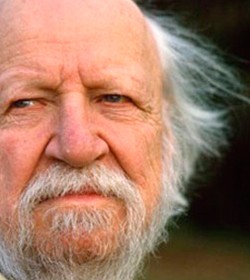

Part of The Coral Island‘s popularity was its clear messages about morality and choices. Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin of the story are tested by their isolation, their encounters with pirates, and their interactions with the cannibalistic inhabitants of nearby islands. Through a series of adventures, the boys’ friendship and loyalty are tested and proved, and at the end the three friends, older and wiser, sail back to England together. Ballantyne included them in a sequel, The Gorilla Hunters, in 1861. In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

Thug Notes: Lord of the Flies

Life in this hood is savage, yo! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Lord of the Flies

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, LOTF