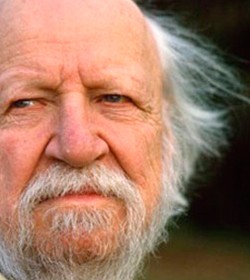

The British novelist William Gerald Golding was born in St. Columb Minor, a village in Cornwall, on September 19, 1911. Golding greatly admired his father, Alec Golding, a distinguished school master who “inhabited a world of sanity and logic and fascination.” His mother, Mildred Golding, was active in the suffragette movement.

Golding entered Oxford University, and to please his parents, he began to study science. After two years, however, he switched to English. He graduated in 1935 with a B.A. degree and diploma in education.

Golding moved to London, where he became a social worker. During this time, he began writing, acting, and producing for a small London theater, bu eventually deferred to family tradition and became a teacher. When World War II began in 1939, he was teaching at Bishop Wordsworth’s school, a boys’ school in Salisbury, Wiltshire.

In 1940, Golding joined the Royal Navy and served on a cruiser. Eventually he became a lieutenant, ending his career in command of a rocket launching craft. During his naval career, Golding saw action against battleships, submarines, and aircraft. He was present at the sinking of the Bismarck and took his rocket-launching craft to Normandy for the D-Day invasion.

In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

In 1961, largely due to the success of Lord of the Flies, Golding was able to leave his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School to become writer-in-residence at Hollins College in Virginia. Thereafter, he became a full-time writer. His later novels include The Spire, The Pyramid, The Scorpion God, Darkness Visible, Rites of Passage, The Paper Men, and Fire Down Below, published four years before his death at 81 years old.

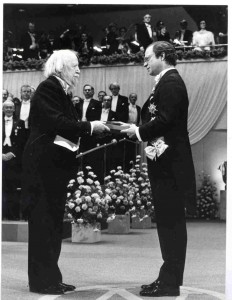

In 1983, Golding received the Nobel Prize for Literature. Of his works in general, he was quoted as saying,

In all books I have suggested a shape in the universe that may, as it were, account for things. The greatest pleasure is…just understanding. And if you can get people to understand their own humanity–well, that’s the job of the writer.

His Nobel lecture discusses various topics and focuses not only on writers, their creations, and the impact that writing has on humanity, but also the mutual responsibility we have for the Earth. He ruminates on the interplay between pessimism (which people assume he has based on the dark focus of his works) and optimism, which he challenges us to embrace and recognize in the power of the written word. Golding says,

Words may, through the devotion, the skill, the passion, and the luck of writers prove to be the most powerful thing in the world. They may move men to speak to each other because some of those words somewhere express not just what the writer is thinking but what a huge segment of the world is thinking. They may allow man to speak to man, the man in the street to speak to his fellow until a ripple becomes a tide running through every nation – of commonsense, of simple healthy caution, a tide that rulers and negotiators cannot ignore so that nation does truly speak unto nation. Then there is hope that we may learn to be temperate, provident, taking no more from nature’s treasury than is our due. It may be by books, stories, poetry, lectures we who have the ear of mankind can move man a little nearer the perilous safety of a warless and provident world.

You may listen to a recording of Golding’s Nobel lecture here.

In the year before his death in 1993, Golding reflected with melancholy on the body of his literary career. Comparing his few works to other writers whose works number in the hundreds, Golding said,

The list makes me more aware of wasted time, the years the locusts have eaten, than of achievement. Seeing them in my mind’s eye I feel a little depressed, like a tourist catching sight of Stonehenge from a distance and for the first time: “not a very impressive scatter of a few stones heaped in a plain without much feature and under a gloomy sky.”

Of course when the tourist (if he can) gets inside the stone circle he will find things much different, and I hope against hope that the same thing can be said of my books.

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

For a commentary on Golding’s reputation in literary circles, check out William Boyd’s “Man as an Island,” published in the New York Times Book Review in 2010.

adapted from material by Jane Gutherman, DPHS English Department

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.