“Like any orthodox moralist Golding insists that Man is

a fallen creature, but he refuses to hypostatize Evil or

to locate it in a dimension of its own.

On the contrary Beelzebub, Lord of the Flies,

is Roger and Jack and you and I,

ready to declare himself as soon as we permit him to.”

—from “The Fables of William Golding” by John Peter, 1957

“Lord of the Flies is a very serious book which has to be introduced seriously. The danger of such an introduction is that it may suggest that the book is stodgy. It is not. It is written with taste and liveliness, the talk is natural, the descriptions of scenery enchanting. It is certainly not a comforting book. But it may help a few grownups to be less complacent and more compassionate, to support Ralph, to respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart. At the present moment (if I may speak personally), it is respect for Piggythat seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders.”

“Lord of the Flies is a very serious book which has to be introduced seriously. The danger of such an introduction is that it may suggest that the book is stodgy. It is not. It is written with taste and liveliness, the talk is natural, the descriptions of scenery enchanting. It is certainly not a comforting book. But it may help a few grownups to be less complacent and more compassionate, to support Ralph, to respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart. At the present moment (if I may speak personally), it is respect for Piggythat seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders.”

—E. M. Forster, introduction to Howard-McCann edition of

Lord of the Flies, 1962

“The South-Sea island setting suggests everyone’s fantasy of lotus-eating escape or refuge from troubles and care. But for Golding this is the sheerest fantasy: there is no escape from the agony of being human, no possibility of erecting utopian political systems where all will go well. Man’s inescapable depravity makes sure “it’s no-go” on Golding’s island just as it does on the various islands visited by Gulliver in Swift’s excoriating examination of the realities of the human condition.”

“The South-Sea island setting suggests everyone’s fantasy of lotus-eating escape or refuge from troubles and care. But for Golding this is the sheerest fantasy: there is no escape from the agony of being human, no possibility of erecting utopian political systems where all will go well. Man’s inescapable depravity makes sure “it’s no-go” on Golding’s island just as it does on the various islands visited by Gulliver in Swift’s excoriating examination of the realities of the human condition.”

—from The Novels of William Golding by S. J. Boyd, 1988

Golding himself had this to say about Lord of the Flies in his essay collection A Moving Target (1985):

More than a quarter of a century ago I sat on one side of the fireplace and my wife on the other. We had just put the children to bed after reading to the elder some adventure story or another—Coral Island, Treasure Island, Pirate Island, Magic Island. God knows what island. Islands have always and for good reason bulked large in the British consciousness. But I was tired of these islands with their paper-cutout goodies and baddies and everything for the best in the best of all possible worlds. I said to my wife, “Wouldn’t it be a good idea if I wrote a story about boys on an island and let them behave the way they really would?” She replied at once, “That’s a first class idea. You write it.” So I sat down and wrote it.

A story about boys, about people who behave as they really would! What sheer hubris! What an assumption of the divine right of authors! How people really behave—whole chapters in that row of books behind my chair do little in the last analysis but agree to or dissent from that first casual remark. How then did I choose a theme? Even then, did I know what I was about? It had taken me more than half a lifetime, two world wars and many years among children before I could make that casual remark because to me the job was so plainly possible.

A story about boys, about people who behave as they really would! What sheer hubris! What an assumption of the divine right of authors! How people really behave—whole chapters in that row of books behind my chair do little in the last analysis but agree to or dissent from that first casual remark. How then did I choose a theme? Even then, did I know what I was about? It had taken me more than half a lifetime, two world wars and many years among children before I could make that casual remark because to me the job was so plainly possible.

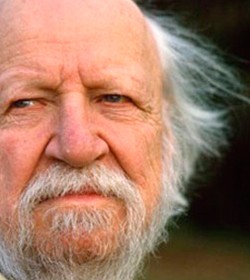

Yet there is something more. In a way the book was to be and did become a distillation from that life. Before the Second World War my generation did on the whole have a liberal and naïve belief in the perfectibility of man. In the war we became if not physically hardened at least morally and inevitably coarsened. After it we saw, little by little, what man could do to man, what the Animal could to do his own species. The years of my life that went into the book were not years of thinking but years of feeling, years of wordless brooding that brought me not so much to an opinion as a stance. It was like lamenting the lost childhood of the world. The theme defeats structuralism for it is an emotion.

Daniel Defoe’s 1719 tale Robinson Crusoe exemplifies many of the hallmarks of these tales we find familiar: a stranded hero, a deserted island, meetings and clashes with various native cultures, and eventual rescue, where the hero returns home a changed man for his experience. The book’s popularity spawned an entire subgenre of literature called Robinsonade, all of which contain a stranded hero, a new beginning, encounters with natives, and commentary on society. These influences can be seen in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a particularly biting piece of satire that uses the castaway motif to savage various aspects of English society, and the modern film Cast Away (2000),

Daniel Defoe’s 1719 tale Robinson Crusoe exemplifies many of the hallmarks of these tales we find familiar: a stranded hero, a deserted island, meetings and clashes with various native cultures, and eventual rescue, where the hero returns home a changed man for his experience. The book’s popularity spawned an entire subgenre of literature called Robinsonade, all of which contain a stranded hero, a new beginning, encounters with natives, and commentary on society. These influences can be seen in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a particularly biting piece of satire that uses the castaway motif to savage various aspects of English society, and the modern film Cast Away (2000),  in which Tom Hanks plays a stranded Federal Express executive who survives alone on an island in the South Pacific for four years with the help of the contents of FedEx packages that washed up on the island with him, including a personified volleyball named Wilson.

in which Tom Hanks plays a stranded Federal Express executive who survives alone on an island in the South Pacific for four years with the help of the contents of FedEx packages that washed up on the island with him, including a personified volleyball named Wilson. Part of The Coral Island‘s popularity was its clear messages about morality and choices. Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin of the story are tested by their isolation, their encounters with pirates, and their interactions with the cannibalistic inhabitants of nearby islands. Through a series of adventures, the boys’ friendship and loyalty are tested and proved, and at the end the three friends, older and wiser, sail back to England together. Ballantyne included them in a sequel, The Gorilla Hunters, in 1861.

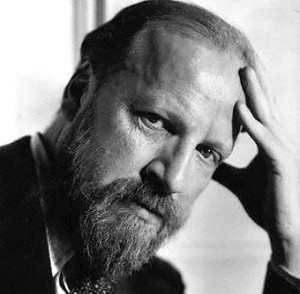

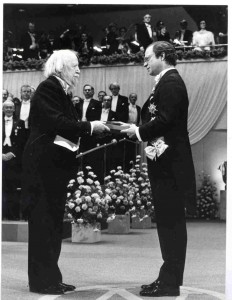

Part of The Coral Island‘s popularity was its clear messages about morality and choices. Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin of the story are tested by their isolation, their encounters with pirates, and their interactions with the cannibalistic inhabitants of nearby islands. Through a series of adventures, the boys’ friendship and loyalty are tested and proved, and at the end the three friends, older and wiser, sail back to England together. Ballantyne included them in a sequel, The Gorilla Hunters, in 1861. In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

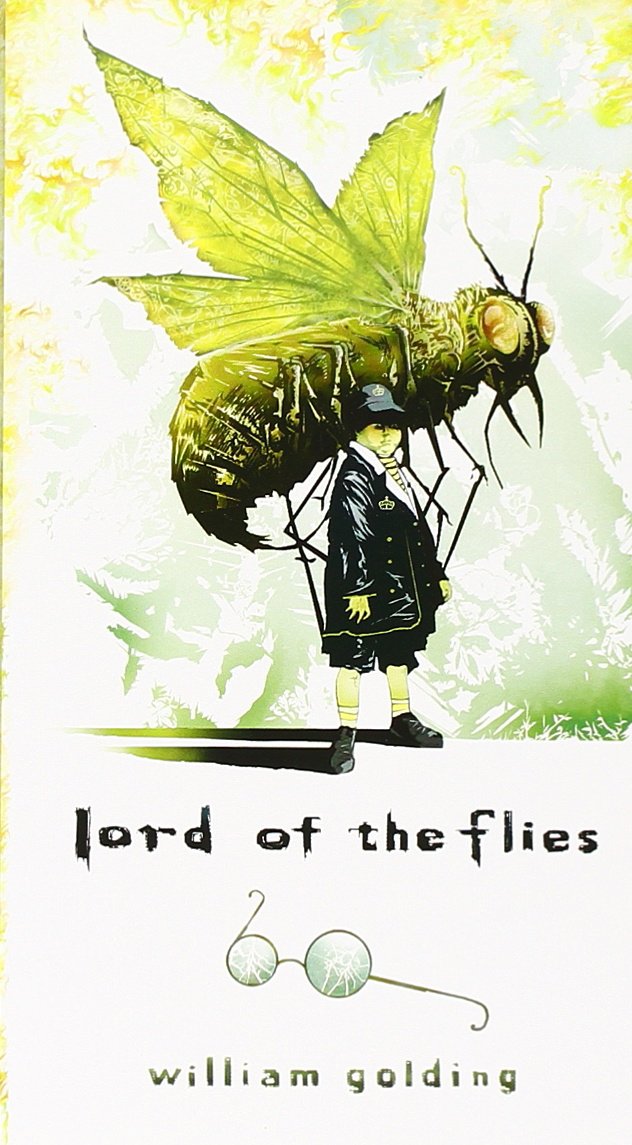

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity. Christopher King, the art director for the American publishing house Melville House, explored some of the design choices for Lord of the Flies in

Christopher King, the art director for the American publishing house Melville House, explored some of the design choices for Lord of the Flies in

In the end, the judges unanimously selected the mixed media work of 15-year-old Sarah Baxter as the contest winner. An interview with Sarah was published in

In the end, the judges unanimously selected the mixed media work of 15-year-old Sarah Baxter as the contest winner. An interview with Sarah was published in  In preparation for our Socratic seminar on Lord of the Flies, please gather textual support that will help you answer the following questions. Although direct quotations are encouraged, references to specific plot elements, characters, etc. in the text will suffice. Remember that the ultimate goal of the seminar is to enhance your knowledge of the work itself, so focus your attention on what occurs in the text rather than speculation drawn from the events in the text.

In preparation for our Socratic seminar on Lord of the Flies, please gather textual support that will help you answer the following questions. Although direct quotations are encouraged, references to specific plot elements, characters, etc. in the text will suffice. Remember that the ultimate goal of the seminar is to enhance your knowledge of the work itself, so focus your attention on what occurs in the text rather than speculation drawn from the events in the text.

Please study the following words for your vocabulary test, which will be given on Thursday, October 16.

Please study the following words for your vocabulary test, which will be given on Thursday, October 16. Please study the following words for your vocabulary test, which will be given on Thursday, October 17.

Please study the following words for your vocabulary test, which will be given on Thursday, October 17.

Thug Notes: Lord of the Flies

Life in this hood is savage, yo! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Lord of the Flies

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, LOTF