OIΔIΠOΥΣ TYPANNOΣ

Still from the 1957 Sir Tyrone Guthrie production of Oedipus Rex.

Like all great plays, Oedipus the King develops a number of important themes. One is stated in the final lines:

And count no man blessed in his life until,

He’s crossed life’s bound unstruck by ruin still.

–Roche translation

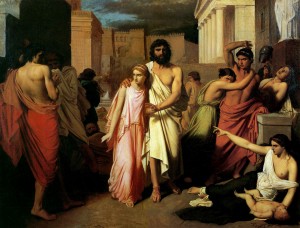

The play shows the fall of Oedipus from the place of highest honor to that of an outcast and demonstrates the uncertainty of human destiny. A second motif is man’s inability to control his own fate. Oedipus is a man who attempts to do his best at all times; he wants to help his people. He has taken what he considers the necessary steps to avoid the terrible fate predicted by the oracle (that he will kill his father and marry his mother). But humans are limited in their vision, no matter how they may attempt to avoid mistakes. The contrast, then, between humans seeking to control their destiny and other forces determining destiny is clearly depicted. But while fate (or the will of the gods) is always the superior force in the play, it works through human beings. It is Jocasta’s attempt to destroy the infant Oedipus, Oedipus’ desire to avoid his parents, and Oedipus’ search for the murderer that lead inevitably to the outcome. At the end, while Oedipus accepts his fate as he must, he still does not see himself entirely under the control of the gods:

Friends, it was Apollo, spirit of Apollo,

He made this evil fructify,

Oh, yes, I pierced my eyes, my useless eyes, why not?

It is significant that no attempt is made to explain why destruction comes to Oedipus. It is implied that man must submit to fate and that in struggling to avoid it he only becomes more entangled. There is then an irrational, or at least an unknowable, force at work. This idea is emphasized through the various attempts to communicate with the gods (through oracles) and to propitiate them. The plague is viewed as a punishment from the gods; the exiling of Oedipus is an attempt to placate them, but no one asks why the gods have decreed Oedipus’ fate. The truth of the oracles is established, but the purpose is unclear. The Greek concept of the gods, however, did not demand that all the gods be benevolent, since all forces were deified whether good or evil. Therefore, a god might visit evil upon human beings, and they had to be constantly on guard not to offend any of the many gods.

It is also possible to interpret this play as suggesting that the gods, rather than having decreed events, have merely foreseen and foretold what the characters will do when confronted with certain problems. Such an interpretation, while it shifts the emphasis somewhat, does not contradict the picture of humans as victims of forces beyond their control, no matter by what name we call those forces.

Another implication, which may not have been a conscious one with Sophocles, is that Oedipus is a scapegoat. The city of Thebes will be saved if one guilty man can be found and punished. Oedipus, in a sense then, takes the sins of the city upon himself, and in his punishment lies the salvation of others. Thus, Oedipus becomes a sacrificial offering to the gods…

Another motif—blindness versus sight—is emphasized in poetic images and in various overt comparisons. A contrast is repeatedly drawn between the physical power of sight and the inner sight of understanding. For example, Tiresias, though blind, can see the truth which escapes Oedipus, while Oedipus, who has penetrated the riddle of the Sphinx, cannot solve the puzzle of his own life. When it is revealed to him, he blinds himself in an act of retribution.

Another motif—blindness versus sight—is emphasized in poetic images and in various overt comparisons. A contrast is repeatedly drawn between the physical power of sight and the inner sight of understanding. For example, Tiresias, though blind, can see the truth which escapes Oedipus, while Oedipus, who has penetrated the riddle of the Sphinx, cannot solve the puzzle of his own life. When it is revealed to him, he blinds himself in an act of retribution.

These themes indicate that Oedipus the King is a comment in part on humankind’s relationship to the gods and on humans’ attempt to control their own destiny. While the Greek views of these problems may not be ours, the problems and many of the implications are still vital and meaningful.

from Brockett, Oscar G. Historical Edition. The Theatre: An Introduction. New York: Holt, 1979.

Here is the closing scene from Igor Stravinsky’s opera Oedipus Rex, filmed in Japan in 1992 with a multiracial case directed by Julie Taymor. Dame Jessye Norman is singing the role of Jocasta, while Philip Langridge (voice) and Min Tanaka (dance) create the role of Oedipus. Opera certainly fits Aristotle’s requirement for spectacle, does it not?

Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this

Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this

Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Katharsis in the house, y’all. Be warned! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, drama, Greek theater, Oedipus Rex