The following questions were considered during the World Café discussion in class today. Selected responses are recorded below.

Is Amanda a good mother?

- YES –> good intentions toward her children, works to support the family, invests time and money into finding Laura a husband, stays with her children despite trouble, genuinely thinks her way is best, stays (unlike their father), tries to help her children advance, won’t allow “crippled” as a descriptor for Laura, comforts Laura at the end

- NO –> very pushy, doesn’t understand Tom’s dreams because she’s worried about Laura and her own situation, overcontrolling, lost in a dream world of the past, actions reflect her desires rather than children’s needs/wishes, superficial, unkind to Tom because he reminds her of her husband, seems more focused on her children’s success than happiness

The Glass Menagerie is a play about _____ because _____.

- Selfish desires – Tom’s and father’s choice to leave, Amanda’s controlling nature

- Regret – Tom regrets leaving Laura

- Misunderstanding – Amanda doesn’t understand either of her children’s wishes

- Appearance vs. Reality – setting of apartment, Laura hiding her disability,

- Deception – Tom’s explanation about where he’s going and why, playing happy family for Jim when they’re not, Laura shrugging off the broken unicorn

- Love and betrayal – characters lying to protect other characters’ feelings, Laura hiding what she’s been doing instead of going to school

- Family – Amanda expecting Tom to be a better man than his father

- Dreams – character’s dreams unspoken to each other, expectations for other characters

- Finding yourself – Tom rejecting the warehouse to write, Amanda clinging to the Southern belle she used to be, Laura retreating into her world of glass

- Illusion – Amanda lives in the past, Laura lives in her glass world, Tom wants to escape to adventure

- Abandonment – Jim abandons Laura (hope), the father abandons the family, Tom abandons Amanda and Laura

Who is the most important character in the play? Explain.

- Amanda – she is the most present of all the characters (appears in most of the scenes), she drives the play and determines the actions of the other characters, she acts as the rock/glue for the family, she presses her desires on her children, she sets the whole play in motion, themes relate back to her relationship with everyone else

- Tom – play is told from his perspective, all conflicts relate back to him, he carries the emotions from the events, when his character leaves the family ceases to exist, focal character, his choice to bring Jim invites the play’s climax, he ends the action on his terms

- Laura – the main action of the play concerns plans for her future, the other characters’ focus in on Laura, the lighting asks the audience to pay attention to her, she has the most emotional development of the characters,

- the father – he’s the reason for their current situation, characters’ choices are viewed in comparison to his, he’s always watching (figuratively) the fallout his leaving created, his absence is the catalyst for both Amanda’s and Tom’s characters

Name and discuss the significance of an important symbol in the play.

- glass menagerie – Laura’s fragility and her hopes/dreams

- father’s picture – constant reminder of his abandonment, foreshadowing of what Tom will become,

- Victrola – Laura’s unwillingness to move and how her life is painfully repetitive

- typewriter – both Tom’s ambitions and Laura’s failed attempts at success,

- merchant marine uniform – Tom’s desire for adventure and foreshadowing of his eventual choice to leave

- blue roses – Laura’s peculiarity and attractiveness,

- fire escape – escaping the family to pursue dreams, when called the “terrace” it romanticizes their reality

- movies – Tom’s escape, further heightening of illusion vs. reality theme

- fancy lamp – illusion that the family is more than it appears to be (happy and comfortable)

- glass unicorn – Laura’s uniqueness, when its horn is broken it shows Laura trying to fit in and be accepted, broken relationship with Jim, her nervousness (when it breaks, she feels more open)

- Amanda’s dress – her clinging to the past, compares her wealthy past to her poorer present

- Jim – the “very ordinary young man” who contrasts greatly with the flawed family

How does the setting function to reveal character and provide insight on theme?

- Gloomy apartment – contributes to bleak and depressing tone, current lifestyle contrasts with the past and reinforces idea of “memory play”

- Living room – one set highlights Laura’s isolation from the world, same set throughout play heightens sense of characters being trapped in their circumstances

- New furnishings – reveals how things aren’t usually as they seem (deception; appearance vs. reality), illusion that they are more than they appear to be, shows Amanda’s wish to be like she was–genteel, Southern, and rich–than what she is

- Fire escape – Tom escaping the family

- St. Louis/South – reinforces traditional roles for women (security, marriage), enhances Amanda’s mentality that Tom and Laura do not share,

- Open windows – lets in music and other pleasures not available to the people in the apartment, reinforces Tom’s wish to escape

Do the images on the screen enhance or detract from the play? Explain.

- ENHANCES –> contributes to the idea of a “memory play” because they are dreamlike like memories, adds to visualization, helps with background knowledge not presented through setting and text, provides insight into what characters are thinking, provides symbolic meaning, reflects how things are remembered, provides comic relief, clarifies possible ambiguities in the dialogue, sets the mood for scenes, adds diversity and interest in the confined setting

- DETRACTS –> pulls attention from what the actors are doing, takes away element of suspense, can be unnecessarily distracting, can dictate opinion of the audience

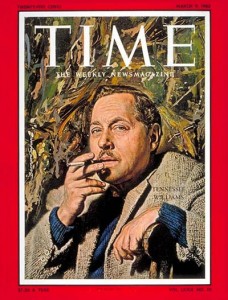

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

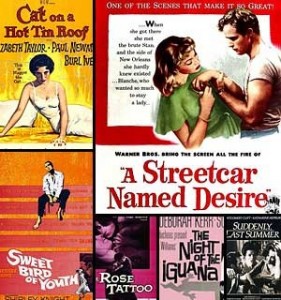

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Mention a Socratic seminar to students, and often the response is just like the one portrayed in “

Mention a Socratic seminar to students, and often the response is just like the one portrayed in “ Seminars will be graded based on both your contributions to the discussion (speaking in class and posting to the discussion board) and the quality of those contributions (specific text references rather than general comments). The fewer comments you make and more general your input, the lower the grade, and vice versa. If you wish a high seminar grade, you will need to contribute thoughtfully and precisely both during the class and online. Ultimately, your seminar participation should reveal your understanding of and thinking about the work in question.

Seminars will be graded based on both your contributions to the discussion (speaking in class and posting to the discussion board) and the quality of those contributions (specific text references rather than general comments). The fewer comments you make and more general your input, the lower the grade, and vice versa. If you wish a high seminar grade, you will need to contribute thoughtfully and precisely both during the class and online. Ultimately, your seminar participation should reveal your understanding of and thinking about the work in question.

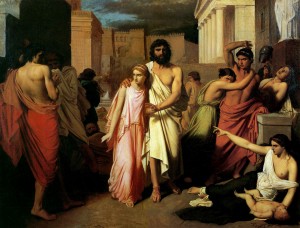

Another motif—blindness versus sight—is emphasized in poetic images and in various overt comparisons. A contrast is repeatedly drawn between the physical power of sight and the inner sight of understanding. For example, Tiresias, though blind, can see the truth which escapes Oedipus, while Oedipus, who has penetrated the riddle of the Sphinx, cannot solve the puzzle of his own life. When it is revealed to him, he blinds himself in an act of retribution.

Another motif—blindness versus sight—is emphasized in poetic images and in various overt comparisons. A contrast is repeatedly drawn between the physical power of sight and the inner sight of understanding. For example, Tiresias, though blind, can see the truth which escapes Oedipus, while Oedipus, who has penetrated the riddle of the Sphinx, cannot solve the puzzle of his own life. When it is revealed to him, he blinds himself in an act of retribution. Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this

Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this  Without a doubt, working with poetry causes AP Lit students the most angst. However, this process does not have to be onerous! Working your way through a poem thoughtfully takes care and attention. Here are two methods you can employ to help you process even the most mysterious of sonnets and have it make (more) sense.

Without a doubt, working with poetry causes AP Lit students the most angst. However, this process does not have to be onerous! Working your way through a poem thoughtfully takes care and attention. Here are two methods you can employ to help you process even the most mysterious of sonnets and have it make (more) sense. There’s a kitchen principle known as “clean as you go” that suggests that if you keep a sink full of hot, soapy water available as you’re cooking, then drop in your messy tools and bowls as you finish using them, the cleanup afterwards goes much faster. The same is true of learning. If you do a little as you go along, there’s much less effort right at the end, whether that means studying for test, writing a paper, or preparing for a seminar. Here are some “learn as you go” principles that will help you be a successful student in AP Lit.

There’s a kitchen principle known as “clean as you go” that suggests that if you keep a sink full of hot, soapy water available as you’re cooking, then drop in your messy tools and bowls as you finish using them, the cleanup afterwards goes much faster. The same is true of learning. If you do a little as you go along, there’s much less effort right at the end, whether that means studying for test, writing a paper, or preparing for a seminar. Here are some “learn as you go” principles that will help you be a successful student in AP Lit.

Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Katharsis in the house, y’all. Be warned! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, drama, Greek theater, Oedipus Rex