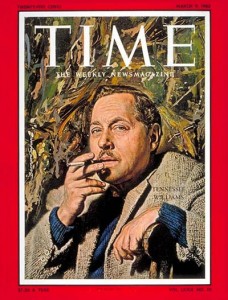

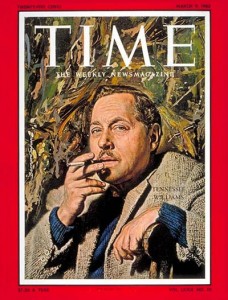

Playwright Tennessee Williams is widely considered one of the twentieth century’s leading lights of American literature. Born in 1911 in Columbus, Mississippi as Thomas Lanier Williams, Tennessee Williams was the middle of three children. His father was a salesman who much preferred life on the road to family life; as a result, Williams was raised primarily by his mother. His early years in Mississippi were relatively carefree. When Williams was seven, the family relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, a change reflecting a difference in the family’s fortunes that Williams understood but resented. He attended college briefly in Missouri until his father withdrew him and demanded he come home and get a job. Williams fell into a depression during this time working at a shoe factory. Although he made time after work to continue his writing, eventually the stress proved too much, and he suffered a nervous breakdown. After recovery he left home, finished college at the University of Iowa, and changed his name to Tennessee Williams.

Playwright Tennessee Williams is widely considered one of the twentieth century’s leading lights of American literature. Born in 1911 in Columbus, Mississippi as Thomas Lanier Williams, Tennessee Williams was the middle of three children. His father was a salesman who much preferred life on the road to family life; as a result, Williams was raised primarily by his mother. His early years in Mississippi were relatively carefree. When Williams was seven, the family relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, a change reflecting a difference in the family’s fortunes that Williams understood but resented. He attended college briefly in Missouri until his father withdrew him and demanded he come home and get a job. Williams fell into a depression during this time working at a shoe factory. Although he made time after work to continue his writing, eventually the stress proved too much, and he suffered a nervous breakdown. After recovery he left home, finished college at the University of Iowa, and changed his name to Tennessee Williams.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Oscar Brockett explains that

By the late 1940s, theatrical realism, the faithful reproduction of real life as accurately as possible on the stage, had begun to modify. Simplification, suggestion, and distortion, borrowed from other artistic movements of the early 20th century, made their way onto stage sets and into character portrayals. Stage settings became more suggestive of locales and functions. Play structures changed as well, often shifting from formal acts into more fluid collections of scenes.

Tennessee Williams’ work employs many of these theatrical devices. Symbolism is found in all of his plays, and his play titles usually indicate some deeper symbolic meaning. Normally, Williams settings are fragmentary and suggestive: consider the fire escapes, alleys, and rooms in The Glass Menagerie that require no scene changes. The use of time is fluid.

Against these suggested backdrops, though, are very lifelike characters dealing with conflicts that represent larger human issues. As Brockett puts it, “…spiritual and material drives are almost always at odds and the resolution of a dramatic action depends on how well the characters can reconcile the demaonds of these two sides of human nature.” Juxtaposition is also evident in how he reveals comic and serious elements. Amanda, for example, can be ridiculous one minute, admirable the next. Williams explores human limitations alongside their aspirations, resulting in plays that can be at once compassionate and bitter. (from The Theatre: An Introduction, Historical Edition. New York: Holt, 1979.)

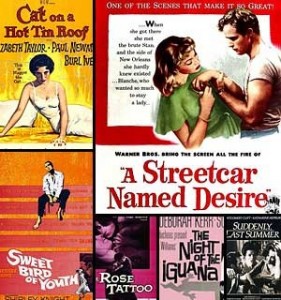

These human limitations are on full display in Williams’ second and perhaps most famous play, A Streetcar Named Desire, which premiered in 1947. In it, genteel Southern manners and brutish reality clash in the characters of Stanley Kowalski, his wife Stella, and her delicate sister Blanche DuBois. Named for the New Orleans streetcar that traveled through the French Quarter to the Bywater district, the play won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It was later made into a film starring Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, and Vivien Leigh, winning Oscars for Hunter and Leigh and a nomination for Best Actor for Brando in addition to other nominations for Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay. A Streetcar Named Desire is widely considered one of the preeminent plays of the 20th century.

These human limitations are on full display in Williams’ second and perhaps most famous play, A Streetcar Named Desire, which premiered in 1947. In it, genteel Southern manners and brutish reality clash in the characters of Stanley Kowalski, his wife Stella, and her delicate sister Blanche DuBois. Named for the New Orleans streetcar that traveled through the French Quarter to the Bywater district, the play won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It was later made into a film starring Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, and Vivien Leigh, winning Oscars for Hunter and Leigh and a nomination for Best Actor for Brando in addition to other nominations for Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay. A Streetcar Named Desire is widely considered one of the preeminent plays of the 20th century.

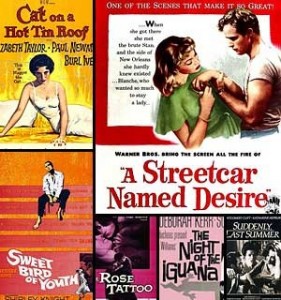

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Williams became a darling of the midcentury literary set. Despite his successes, he battled a lifelong dependency on alcohol and drugs and was at one point committed to the hospital by his brother to recover. Although he worked feverishly after his release in the mid-1970s, his demons caught up with him. In 1983, Tennessee Williams was found dead in his New York apartment, surrounded by pills and empty bottles. He’d choked to death on a plastic bottle cap.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this

Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this

Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Katharsis in the house, y’all. Be warned! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, drama, Greek theater, Oedipus Rex