On November 1, 1604, Master of Revels Edmund Tilney notes that a play titled The Moor of Venice was performed at Whitehall Palace for King James I. In the four hundred-plus years since, Othello has become one of the best-known and regarded of Shakespeare’s plays. It has also presented a number of questions regarding its central character, Othello the Moor.

During the Elizabethan era, the word “Moor” could have meant several things. Scholar Ben Arogundade notes that “[‘Moor’] was first used to describe the natives of Mauretania — the region of North Africa which today corresponds to Morocco and Algeria. It was later applied to people of Berber and Arab origin, who conquered and ruled the Iberian Peninsula — the area now known as Spain and Portugal — for nearly eight centuries. From the Middle Ages onwards the Moors were commonly regarded as black Africans, and the word was used alongside the terms ‘negro,’ ‘Ethiopian’ and ‘Blackamoor’ as a racial identifier.

At the time of performance, London audiences would have been familiar with a man named Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri, who arrived in 1600 as an ambassador of the Sa’adian ruler of Morocco, Mulay Ahmed al-Mansur. England’s various alliances with the countries of North Africa familiarized the Elizabethan world with their traditions. Islamic and Muslim characters appeared in plays as early as Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great in 1587, and in more than sixty plays from the next ten years, characters described with words like “Moors,” “Saracens,” “Turks,” and “Persians” appeared, including several of Shakespeare’s own. So it is not without historical or literary precedent that some critics believe that the character of Othello is intended to be a North African man of Arab descent.

At the time of performance, London audiences would have been familiar with a man named Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri, who arrived in 1600 as an ambassador of the Sa’adian ruler of Morocco, Mulay Ahmed al-Mansur. England’s various alliances with the countries of North Africa familiarized the Elizabethan world with their traditions. Islamic and Muslim characters appeared in plays as early as Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great in 1587, and in more than sixty plays from the next ten years, characters described with words like “Moors,” “Saracens,” “Turks,” and “Persians” appeared, including several of Shakespeare’s own. So it is not without historical or literary precedent that some critics believe that the character of Othello is intended to be a North African man of Arab descent.

The far more common interpretation, however, is for Othello to be viewed as a sub-Saharan African with black features. It is this portrayal that is most commonly found in modern productions of the play. From Shakespeare’s time until the early 1800s, this meant that the actor tackling the role would have played it in blackface makeup.

It wasn’t until 1826 that Othello was finally played by a black performer: American actor Ira Aldridge. Aldridge emigrated to London at age 17 to pursue his acting career. But his groundbreaking performance wasn’t without criticism. The 1933 performance in Covent Garden was criticized by the paper The Anthenaeum because of the startling new reality of Ellen Tree, the white actress playing Desdemona, being manhandled by Aldridge. And although Aldridge became quite famous in London and abroad, it took nearly a hundred years before another black actor became attached to the role. According to writer Samantha Ellis, “In 1825, the pro-slavery lobby had closed [Aldridge’s] production and the Times‘s critic had written: ‘Owing to the shape of his lips it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English.’ No wonder it took almost a century for another black actor to brave the part.”

Perhaps the best-known Othello in the United States is the renowned actor Paul Robeson. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson had built an international reputation not only from his role in the musical Show Boat, but as an athlete and an attorney. Robeson had a commanding physical presence that suited the role perfectly, but his casting against the young British actress Peggy Ashcroft in 1930 was not without controversy. Technical issues like poor staging and difficult acoustics made performing difficult. But no one argued with the power of Robeson’s performance. Ivor Brown, the critic for The Observer, described Robeson as “… an oak…a superb giant of the woods for the great hurricane of tragedy to whisper through, then rage upon, then break.” Audiences at the premiere gave Robeson twenty curtain calls. But, given the societal segregation of the time, Robeson had detractors as well who criticized everything from his interpretation of the role to how he pronounced the words of Shakespeare’s text. Samantha Ellis writes:

Perhaps the best-known Othello in the United States is the renowned actor Paul Robeson. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson had built an international reputation not only from his role in the musical Show Boat, but as an athlete and an attorney. Robeson had a commanding physical presence that suited the role perfectly, but his casting against the young British actress Peggy Ashcroft in 1930 was not without controversy. Technical issues like poor staging and difficult acoustics made performing difficult. But no one argued with the power of Robeson’s performance. Ivor Brown, the critic for The Observer, described Robeson as “… an oak…a superb giant of the woods for the great hurricane of tragedy to whisper through, then rage upon, then break.” Audiences at the premiere gave Robeson twenty curtain calls. But, given the societal segregation of the time, Robeson had detractors as well who criticized everything from his interpretation of the role to how he pronounced the words of Shakespeare’s text. Samantha Ellis writes:

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, WA Darlington felt that Robeson was a “really memorable” Othello precisely because he was black: “By reason of his race Mr Robeson is able to surmount the difficulties which English actors generally find in the part.” While other Othellos had seemed illogically jealous, Robeson’s jealousy seemed real, because: “Mr Robeson…comes of a race whose characteristic is to keep control of its passions only to a point, and after that point to throw control to the winds.” It was a “fine” performance and “the much-debated question whether Shakespeare meant Othello to be a negro or an Arab can be left to the professors.” Baughan, in contrast, stated baldly: “I agree with Coleridge that Othello must not be conceived as a negro, but as a high and chivalrous Moorish chief.”

Only the Express‘s critic seemed to think the casting of a black actor was a historic event. He reported overhearing people saying “Why should a black actor be allowed to kiss a white actress?” and his review, subtitled “Coloured Audience in the Stalls,” concluded that Robeson had “triumphed as a negro Moor, black, swarthy, muscular, a real man of deep colour.”

Robeson himself enjoyed playing Othello, and it became his signature role for the remainder of his career. As Ellis notes, “For Robeson, it was more than just a part: it was, as he once said, ‘killing two birds with one stone. I’m acting and I’m talking for the negroes in the way only Shakespeare can.'”

Despite the positive reception of an African-American actor in the role, the Oscar-nominated 1965 production (the highest number for a Shakespeare film in history) starring Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Dame Maggie Smith as Desdemona reverted to type: The famous English actor played the role in makeup. This was the first cinematic Othello to be shot using color film, and Oliver was as meticulous about that as he was about developing the physical character through a deep voice and a special walk. He stated in an interview with Life magazine in 1964 that, “The whole [makeup] will be in the lips and the colour. I’ve been looking at Negroes lips every time I see them on the train or anywhere, and actually, their lips seems black or blueberry-coloured, really, rather than red. But of course the variations are enormous. I’ll just use a little tiny touch of lake and a lot more brown and a little mauve.”

Despite the positive reception of an African-American actor in the role, the Oscar-nominated 1965 production (the highest number for a Shakespeare film in history) starring Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Dame Maggie Smith as Desdemona reverted to type: The famous English actor played the role in makeup. This was the first cinematic Othello to be shot using color film, and Oliver was as meticulous about that as he was about developing the physical character through a deep voice and a special walk. He stated in an interview with Life magazine in 1964 that, “The whole [makeup] will be in the lips and the colour. I’ve been looking at Negroes lips every time I see them on the train or anywhere, and actually, their lips seems black or blueberry-coloured, really, rather than red. But of course the variations are enormous. I’ll just use a little tiny touch of lake and a lot more brown and a little mauve.”

But as well-received as the production was by the Oscar crowd, its release during the height of the Civil Rights Movement dampened its reception with audiences. Arongundade remarks that “…[Olivier’s] blackface portrayal troubled American critics when the film opened there in 1966…sensitivities about black identity were at their height, and many saw Olivier’s chosen aesthetic as outdated.”

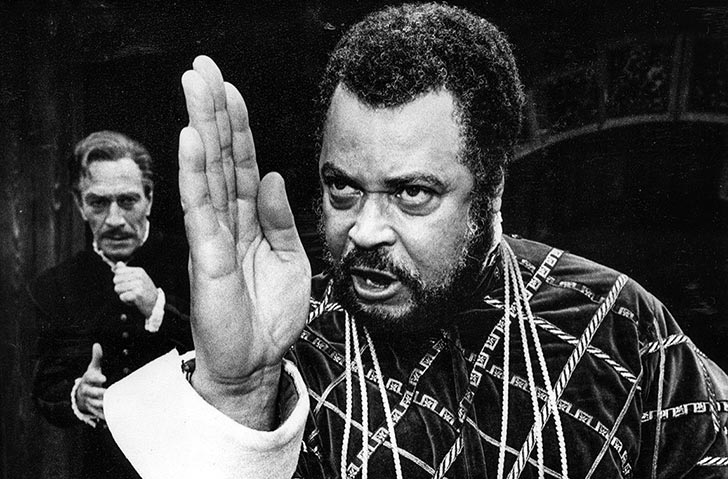

Perhaps the pushback against the Olivier production opened the door for the now generally-accepted casting of an African-American actor in the role. Famous Othellos of the last several decades include theater luminaries like James Earl Jones, Oscar-nominated actor Laurence Fishburne in a stellar 1995 production starring Kenneth Branagh as Iago and French actress Irene Jacob as Desdemona, and young actor Mekhi Phifer in “O,” a contemporary version that transforms the military conflict into a basketball rivalry set in a high school. Other famous actors who have played Othello include Orson Welles, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Eamonn Walker in a 2001 TV movie co-starring Christopher Eccleston (best known as the ninth Doctor Who) as Iago, which transplants the action from Venice and Cyprus to a London police station.

Perhaps the pushback against the Olivier production opened the door for the now generally-accepted casting of an African-American actor in the role. Famous Othellos of the last several decades include theater luminaries like James Earl Jones, Oscar-nominated actor Laurence Fishburne in a stellar 1995 production starring Kenneth Branagh as Iago and French actress Irene Jacob as Desdemona, and young actor Mekhi Phifer in “O,” a contemporary version that transforms the military conflict into a basketball rivalry set in a high school. Other famous actors who have played Othello include Orson Welles, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Eamonn Walker in a 2001 TV movie co-starring Christopher Eccleston (best known as the ninth Doctor Who) as Iago, which transplants the action from Venice and Cyprus to a London police station.

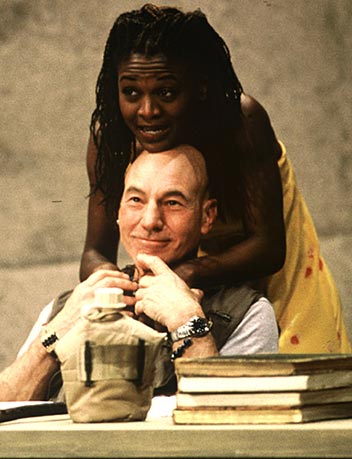

Modern theater companies wishing to explore the themes of Othello in new ways have explored variant casting. A 1997 production of the play in Baltimore starred Patrick Stewart as Othello, the lone white actor in a racially-flipped cast in which every other actor was African-American. Stewart, pictured here with Patrice Johnson as Desdemona, explained, “One of my hopes for this production is that it will continue to say what a conventional production of Othello would say about racism and prejudice… To replace the black outsider with a white man in a black society will, I hope, encourage a much broader view of the fundamentals of racism.” A review in the Baltimore Sun said, “It is a tribute to the concept as well as Stewart’s performance that the initial awkwardness falls away as early as his second scene…Stewart, who possesses a calm assuredness at the start of the play, lets the theater’s predominantly white audience experience how completely foreign Othello must have felt in a society where he was viewed as the outsider.”

Speaking of foreign: A German production at the Deutsches Theatre in 2001 pushed the boundaries of the character by not only casting a white actor as Othello, but a female one. This more avant-garde production starring actress Susanne Wolff sees Wolff utter her lines in varying costumes progressing from a simple black-and-white shirt and pants ensemble to—believe it or not—a gorilla suit intended to show Othello’s shift from loving partner to a more animalistic creature bent on vengeance. Blogger/reviewer Andrew Haydon says about the production, “Okay, there are two headlines to choose from here: 1) I’ve just seen the best production of Othello I’ve ever seen. 2) I’ve just seen a production of Othello in which Othello is played by a white woman in a gorilla costume. My job, then, is to explain how (2) manages to be (1).”

Speaking of foreign: A German production at the Deutsches Theatre in 2001 pushed the boundaries of the character by not only casting a white actor as Othello, but a female one. This more avant-garde production starring actress Susanne Wolff sees Wolff utter her lines in varying costumes progressing from a simple black-and-white shirt and pants ensemble to—believe it or not—a gorilla suit intended to show Othello’s shift from loving partner to a more animalistic creature bent on vengeance. Blogger/reviewer Andrew Haydon says about the production, “Okay, there are two headlines to choose from here: 1) I’ve just seen the best production of Othello I’ve ever seen. 2) I’ve just seen a production of Othello in which Othello is played by a white woman in a gorilla costume. My job, then, is to explain how (2) manages to be (1).”

Sources:

Ben Arungodade, “What Was Othello’s Race?” and “The 18 Most Memorable Othello Actors Performances”

Baltimore Sun review of Sir Patrick Stewart Othello

Jerry Brotton, “Is This the Real Model for Othello?”

Samantha Ellis, “Paul Robeson in Othello, Savoy Theatre, 1930”

Emily Anne Gibson, “The Face of Othello”

Andrew Haydon, “Othello – Deutsches Theatre”

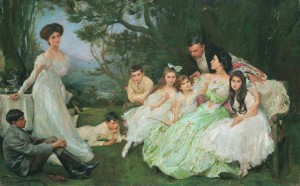

Othello Relating His Adventures to Desdemona by Carl Ludwig Friedrich Becker, 1880.

I HAVE two babies; I hope they may never know how warmly at this moment I hate them. I have a husband; we were married because we were very much in love-and him I hate too. I have a large stock of relatives, and them I hate with the heart and should hate with the hand if I had not the misfortune to be well brought up. This emotion of mine, especially in connection with my spouse and offspring, is, up to the present, local and temporary; indeed I think it will not grow into a permanent hatred, but will gradually assume two peculiar forms: toward my children a passionate and slavish devotion, which will make me resent my daughters-in-law; and toward my husband regards, reasonably kind, which will be reciprocated. My feeling toward my relatives, on the other hand, is becoming quite, quite fixed.

I HAVE two babies; I hope they may never know how warmly at this moment I hate them. I have a husband; we were married because we were very much in love-and him I hate too. I have a large stock of relatives, and them I hate with the heart and should hate with the hand if I had not the misfortune to be well brought up. This emotion of mine, especially in connection with my spouse and offspring, is, up to the present, local and temporary; indeed I think it will not grow into a permanent hatred, but will gradually assume two peculiar forms: toward my children a passionate and slavish devotion, which will make me resent my daughters-in-law; and toward my husband regards, reasonably kind, which will be reciprocated. My feeling toward my relatives, on the other hand, is becoming quite, quite fixed.

The truth is, however, that it is not a floor-scrubber and dishwasher that I desire. I could get along with that work or leave it happily undone. It is the care of two children under three that concerns me. It is unremitting and nerve-tearing, and the day in and day out of it is under mining mercilessly my ability to be lovable and to love. Furthermore, I have not the qualifications that would justify entrusting me with sole responsibility for the growth of human beings. Maternal instinct I have in normal amount; I could be trusted to rescue my infants from a burning building, but that is a very different matter from knowing what to do with twenty-four hours’ worth of bodily and mental development every day. I do not want a nursemaid; I have no training for my job, but I have an occasional vagrant idea, and it does not appeal to me to exchange my services to my offspring for those of a hand-maiden with neither training nor ideas. The helper for me should be a trained psychologist, a child-lover, to be sure, but a child-lover with expert knowledge of the needs of growing minds. She should have also training in the treatment of the smaller physical ailments of children. She ought to cost me two thousand dollars a year, but in the present state of women’s wages I have no doubt I could get her for a thousand. And I want her only half the day-five hundred dollars. Our income is sixteen hundred.

The truth is, however, that it is not a floor-scrubber and dishwasher that I desire. I could get along with that work or leave it happily undone. It is the care of two children under three that concerns me. It is unremitting and nerve-tearing, and the day in and day out of it is under mining mercilessly my ability to be lovable and to love. Furthermore, I have not the qualifications that would justify entrusting me with sole responsibility for the growth of human beings. Maternal instinct I have in normal amount; I could be trusted to rescue my infants from a burning building, but that is a very different matter from knowing what to do with twenty-four hours’ worth of bodily and mental development every day. I do not want a nursemaid; I have no training for my job, but I have an occasional vagrant idea, and it does not appeal to me to exchange my services to my offspring for those of a hand-maiden with neither training nor ideas. The helper for me should be a trained psychologist, a child-lover, to be sure, but a child-lover with expert knowledge of the needs of growing minds. She should have also training in the treatment of the smaller physical ailments of children. She ought to cost me two thousand dollars a year, but in the present state of women’s wages I have no doubt I could get her for a thousand. And I want her only half the day-five hundred dollars. Our income is sixteen hundred.

Key Scenes in Othello

Consider/review these scenes as you complete your Major Works Data Sheet for Othello and prepare for the seminar:

Act I, Scene 3 – Othello and Desdemona’s stories of their love; The Duke’s and Brabantio’s warnings to Othello; Iago’s advice to Roderigo; Iago’s final speech

Act II, Scene 1 – Iago, Emilia, and Desdemona speaking of men and women; Iago’s speeches regarding his developing plan of revenge

Act II, Scene 3 – Cassio’s downfall and Iago’s advice to Cassio

Act III, Scene 3 – Iago plants and waters the seed of jealousy

Act III, Scene 4 – Othello confronts Desdemona about the handkerchief

Act IV, Scene 1 – Iago “proves” Cassio’s betrayal; Othello and Iago make plans

Act IV, Scene 3 – Desdemona and Emilia talk of men and women

Act V, Scene 1 – Iago puts his final plan into action

Act V, Scene 2 – Othello carries through with his part of the bargain; Iago’s plot is revealed and tragedy befalls the cast

Othello’s Lamentation by William Salter, 1857, from the Folger Library Collection

Comments Off on Key Scenes in Othello

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, discussion, Othello, plays, reading, sources