Mention a Socratic seminar to students, and often the response is just like the one portrayed in “Oh God, Teacher Arranged Desks in a Giant Circle” from The Onion. In other words, uncertainty, anxiety, and even panic. But if you enter a seminar prepared, you’ll find your fears allayed and, I hope, your knowledge of the work we’re discussing extended and deepened.

Mention a Socratic seminar to students, and often the response is just like the one portrayed in “Oh God, Teacher Arranged Desks in a Giant Circle” from The Onion. In other words, uncertainty, anxiety, and even panic. But if you enter a seminar prepared, you’ll find your fears allayed and, I hope, your knowledge of the work we’re discussing extended and deepened.

The first thing you need to understand is that a Socratic seminar is not a debate. The point is not to win an argument. Instead, a Socratic seminar aims to deepen understanding through discussion and questioning. A more detailed explanation can be found here: Dialogue vs. Debate. Seminar participation will be graded like a test, and there are three keys that will help you do your best.

PREPARATION

Come to the seminar prepared. Students should have their Six Pack Sheet for the work completed as fully as possible, including their ideas on motifs and symbols, references to important scenes/conversations, and character information. Crafting thoughtful questions can also provide you with something to share. Remember that your questions should explore WHAT IS in the work (cause and effect, character motivation, etc.) and not WHAT IF (speculation based on something that occurs). We’re discussing the work as presented, not writing fanfic. The ultimate goal is to discern an appropriate meaning of the work as a whole (MOWAW) that can be supported by textual evidence.

PARTICIPATION

Most seminars will be conducted over two days. On the first day, we will open with a question round. Everyone present will share one of the questions they have prepared on their Six Pack Sheet. We will then select a question to kick off the day’s discussion.

During the discussion, your job is to listen and connect. One person should speak at a time. Comments should be directed to the class as a whole rather than to the teacher, who acts as a facilitator rather than a leader. Comments should ADD something new to the conversation, REFER to the text to clarify or support, or EXTEND what another student has introduced. Please take notes on what you hear using the appropriate field in the Six Pack Sheet. Day 2 of the seminar will begin with a comment round, with everyone sharing something interesting from the first day that they found thought provoking or wish to discuss further. Six Pack Sheets with their seminar notes will be submitted to Canvas at the end of Day 2.

While you are speaking, I will be observing and making notes on your seminar input and behavior. Positive behaviors that will earn you points include the following:

• offers new idea

• asks a new or follow-up question

• refers to the text

• paraphrases and adds to another’s idea

• encourages others to speak

Please avoid interrupting others, side conversations, and dominating the conversation—the best seminars allow everyone a chance to speak and respond. Conversely, don’t sit in silence. Have a question or quotation ready to go if you don’t feel confident expressing yourself off the cuff.

FOLLOWUP

To extend the conversation and provide a record for review later, we will also conduct a followup discussion using Canvas. All students will be expected to contribute to the online discussion even if they spoke in class. The online discussion will be open for a few days after the in-class seminar is concluded. Once the online discussion closes, seminar grades will be finalized.

Seminars will be graded based on both your contributions to the discussion (speaking in class and posting to the discussion board) and the quality of those contributions (specific text references rather than general comments). The fewer comments you make and more general your input, the lower the grade, and vice versa. If you wish a high seminar grade, you will need to contribute thoughtfully and precisely both during the class and online. Ultimately, your seminar participation should reveal your understanding of and thinking about the work in question.

Seminars will be graded based on both your contributions to the discussion (speaking in class and posting to the discussion board) and the quality of those contributions (specific text references rather than general comments). The fewer comments you make and more general your input, the lower the grade, and vice versa. If you wish a high seminar grade, you will need to contribute thoughtfully and precisely both during the class and online. Ultimately, your seminar participation should reveal your understanding of and thinking about the work in question.

If you are absent from class on a seminar day, you will be expected to increase your participation in the online conversation. In addition, you will have a separate written assignment to complete.

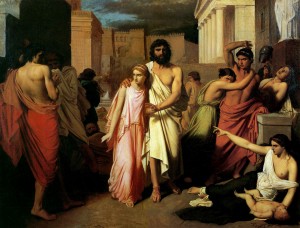

Another motif—blindness versus sight—is emphasized in poetic images and in various overt comparisons. A contrast is repeatedly drawn between the physical power of sight and the inner sight of understanding. For example, Tiresias, though blind, can see the truth which escapes Oedipus, while Oedipus, who has penetrated the riddle of the Sphinx, cannot solve the puzzle of his own life. When it is revealed to him, he blinds himself in an act of retribution.

Another motif—blindness versus sight—is emphasized in poetic images and in various overt comparisons. A contrast is repeatedly drawn between the physical power of sight and the inner sight of understanding. For example, Tiresias, though blind, can see the truth which escapes Oedipus, while Oedipus, who has penetrated the riddle of the Sphinx, cannot solve the puzzle of his own life. When it is revealed to him, he blinds himself in an act of retribution. Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this

Drama as we know it today has its roots in the plays of ancient Greece. These plays were created as part of the worship of Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine. The four Dionysian festivals, the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria, and the City (or Great) Dionysia, celebrated the god, with plays performed in competition at all but the Anthesteria. Playwrights in competition would be expected to create and produce three tragedies and a satyr play. An excellent explanation of this process may be found at this  Without a doubt, working with poetry causes AP Lit students the most angst. However, this process does not have to be onerous! Working your way through a poem thoughtfully takes care and attention. Here are two methods you can employ to help you process even the most mysterious of sonnets and have it make (more) sense.

Without a doubt, working with poetry causes AP Lit students the most angst. However, this process does not have to be onerous! Working your way through a poem thoughtfully takes care and attention. Here are two methods you can employ to help you process even the most mysterious of sonnets and have it make (more) sense. There’s a kitchen principle known as “clean as you go” that suggests that if you keep a sink full of hot, soapy water available as you’re cooking, then drop in your messy tools and bowls as you finish using them, the cleanup afterwards goes much faster. The same is true of learning. If you do a little as you go along, there’s much less effort right at the end, whether that means studying for test, writing a paper, or preparing for a seminar. Here are some “learn as you go” principles that will help you be a successful student in AP Lit.

There’s a kitchen principle known as “clean as you go” that suggests that if you keep a sink full of hot, soapy water available as you’re cooking, then drop in your messy tools and bowls as you finish using them, the cleanup afterwards goes much faster. The same is true of learning. If you do a little as you go along, there’s much less effort right at the end, whether that means studying for test, writing a paper, or preparing for a seminar. Here are some “learn as you go” principles that will help you be a successful student in AP Lit.

Struggle

Struggle Sex

Sex Death

Death Oscar Wilde, the Irish playwright who became the darling of British high society, is probably the best-known and most-quoted satirist of the late 19th century. Born in Dublin, Ireland in 1864, Wilde became a well-known lecturer, essayist, and playwright who enjoyed near-universal popularity until the shocking trial that ended his literary career and, not long after, his life.

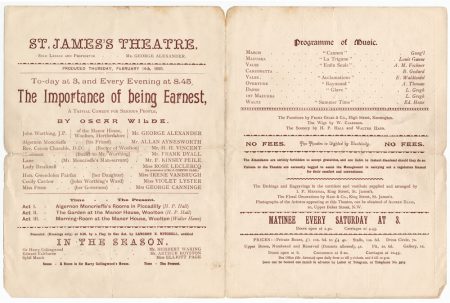

Oscar Wilde, the Irish playwright who became the darling of British high society, is probably the best-known and most-quoted satirist of the late 19th century. Born in Dublin, Ireland in 1864, Wilde became a well-known lecturer, essayist, and playwright who enjoyed near-universal popularity until the shocking trial that ended his literary career and, not long after, his life. The next year, Wilde’s first play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, made its debut to great acclaim. Playwriting became Wilde’s preferred literary style. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed in short order by A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and both An Ideal Husband and his most famous play, The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Each of these works skewered the pretensions of British high society through clever wordplay and Wilde’s satirical wit.

The next year, Wilde’s first play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, made its debut to great acclaim. Playwriting became Wilde’s preferred literary style. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed in short order by A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and both An Ideal Husband and his most famous play, The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Each of these works skewered the pretensions of British high society through clever wordplay and Wilde’s satirical wit.

Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Katharsis in the house, y’all. Be warned! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Oedipus Rex

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, drama, Greek theater, Oedipus Rex