In this sketch, comedian Rowan Atkinson (better known as Mr. Bean or the voice of Zazu, the majordomo bird in The Lion King) explains Elizabethan theater, including the roles of king and messenger and the importance of having a poison checker. Enjoy!

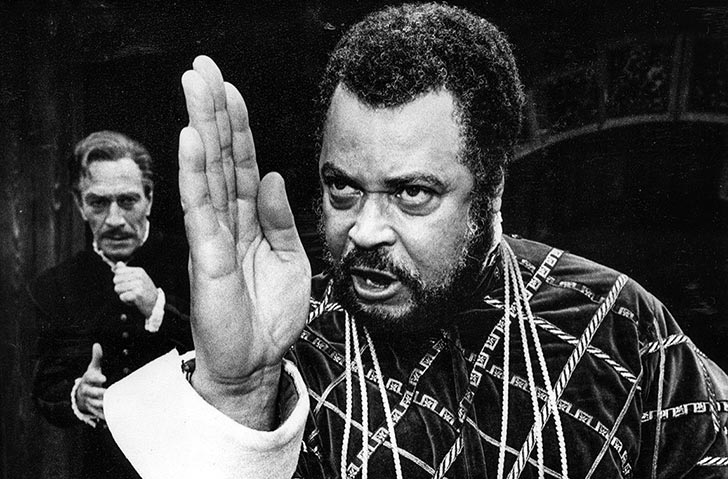

Robeson himself enjoyed playing Othello, and it became his signature role for the remainder of his career. As Ellis notes, “For Robeson, it was more than just a part: it was, as he once said, ‘killing two birds with one stone. I’m acting and I’m talking for the negroes in the way only Shakespeare can.'”

Despite the positive reception of an African-American actor in the role, the Oscar-nominated 1965 production (the highest number for a Shakespeare film in history) starring Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Dame Maggie Smith as Desdemona reverted to type: The famous English actor played the role in makeup. This was the first cinematic Othello to be shot using color film, and Oliver was as meticulous about that as he was about developing the physical character through a deep voice and a special walk. He stated in an interview with Life magazine in 1964 that, “The whole [makeup] will be in the lips and the colour. I’ve been looking at Negroes lips every time I see them on the train or anywhere, and actually, their lips seems black or blueberry-coloured, really, rather than red. But of course the variations are enormous. I’ll just use a little tiny touch of lake and a lot more brown and a little mauve.”

Despite the positive reception of an African-American actor in the role, the Oscar-nominated 1965 production (the highest number for a Shakespeare film in history) starring Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Dame Maggie Smith as Desdemona reverted to type: The famous English actor played the role in makeup. This was the first cinematic Othello to be shot using color film, and Oliver was as meticulous about that as he was about developing the physical character through a deep voice and a special walk. He stated in an interview with Life magazine in 1964 that, “The whole [makeup] will be in the lips and the colour. I’ve been looking at Negroes lips every time I see them on the train or anywhere, and actually, their lips seems black or blueberry-coloured, really, rather than red. But of course the variations are enormous. I’ll just use a little tiny touch of lake and a lot more brown and a little mauve.”

But as well-received as the production was by the Oscar crowd, its release during the height of the Civil Rights Movement dampened its reception with audiences. Arongundade remarks that “…[Olivier’s] blackface portrayal troubled American critics when the film opened there in 1966…sensitivities about black identity were at their height, and many saw Olivier’s chosen aesthetic as outdated.”

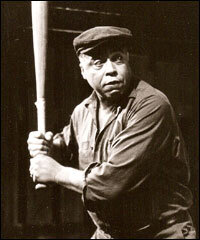

Perhaps the pushback against the Olivier production opened the door for the now generally-accepted casting of an African-American actor in the role. Famous Othellos of the last several decades include theater luminaries like James Earl Jones, Oscar-nominated actor Laurence Fishburne in a stellar 1995 production starring Kenneth Branagh as Iago and French actress Irene Jacob as Desdemona, and young actor Mekhi Phifer in “O,” a contemporary version that transforms the military conflict into a basketball rivalry set in a high school. Other famous actors who have played Othello include Orson Welles, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Eamonn Walker in a 2001 TV movie co-starring Christopher Eccleston (best known as the ninth Doctor Who) as Iago, which transplants the action from Venice and Cyprus to a London police station.

Perhaps the pushback against the Olivier production opened the door for the now generally-accepted casting of an African-American actor in the role. Famous Othellos of the last several decades include theater luminaries like James Earl Jones, Oscar-nominated actor Laurence Fishburne in a stellar 1995 production starring Kenneth Branagh as Iago and French actress Irene Jacob as Desdemona, and young actor Mekhi Phifer in “O,” a contemporary version that transforms the military conflict into a basketball rivalry set in a high school. Other famous actors who have played Othello include Orson Welles, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Eamonn Walker in a 2001 TV movie co-starring Christopher Eccleston (best known as the ninth Doctor Who) as Iago, which transplants the action from Venice and Cyprus to a London police station.

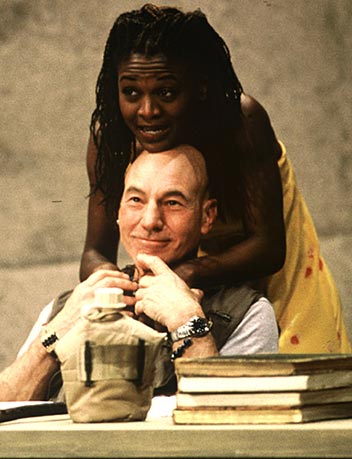

Modern theater companies wishing to explore the themes of Othello in new ways have explored variant casting. A 1997 production of the play in Baltimore starred Patrick Stewart as Othello, the lone white actor in a racially-flipped cast in which every other actor was African-American. Stewart, pictured here with Patrice Johnson as Desdemona, explained, “One of my hopes for this production is that it will continue to say what a conventional production of Othello would say about racism and prejudice… To replace the black outsider with a white man in a black society will, I hope, encourage a much broader view of the fundamentals of racism.” A review in the Baltimore Sun said, “It is a tribute to the concept as well as Stewart’s performance that the initial awkwardness falls away as early as his second scene…Stewart, who possesses a calm assuredness at the start of the play, lets the theater’s predominantly white audience experience how completely foreign Othello must have felt in a society where he was viewed as the outsider.”

Speaking of foreign: A German production at the Deutsches Theatre in 2001 pushed the boundaries of the character by not only casting a white actor as Othello, but a female one. This more avant-garde production starring actress Susanne Wolff sees Wolff utter her lines in varying costumes progressing from a simple black-and-white shirt and pants ensemble to—believe it or not—a gorilla suit intended to show Othello’s shift from loving partner to a more animalistic creature bent on vengeance. Blogger/reviewer Andrew Haydon says about the production, “Okay, there are two headlines to choose from here: 1) I’ve just seen the best production of Othello I’ve ever seen. 2) I’ve just seen a production of Othello in which Othello is played by a white woman in a gorilla costume. My job, then, is to explain how (2) manages to be (1).”

Speaking of foreign: A German production at the Deutsches Theatre in 2001 pushed the boundaries of the character by not only casting a white actor as Othello, but a female one. This more avant-garde production starring actress Susanne Wolff sees Wolff utter her lines in varying costumes progressing from a simple black-and-white shirt and pants ensemble to—believe it or not—a gorilla suit intended to show Othello’s shift from loving partner to a more animalistic creature bent on vengeance. Blogger/reviewer Andrew Haydon says about the production, “Okay, there are two headlines to choose from here: 1) I’ve just seen the best production of Othello I’ve ever seen. 2) I’ve just seen a production of Othello in which Othello is played by a white woman in a gorilla costume. My job, then, is to explain how (2) manages to be (1).”

Sources:

Ben Arungodade, “What Was Othello’s Race?” and “The 18 Most Memorable Othello Actors Performances”

Baltimore Sun review of Sir Patrick Stewart Othello

Jerry Brotton, “Is This the Real Model for Othello?”

Samantha Ellis, “Paul Robeson in Othello, Savoy Theatre, 1930”

Emily Anne Gibson, “The Face of Othello”

Andrew Haydon, “Othello – Deutsches Theatre”

Othello Relating His Adventures to Desdemona by Carl Ludwig Friedrich Becker, 1880.

Mary Alice, James Earl Jones and Courtney Vance in Fences at Yale Repertory Theatre. William B. Carter, 1985. Courtesy of Yale Repertory Theatre

Mary Alice, James Earl Jones and Courtney Vance in Fences at Yale Repertory Theatre. William B. Carter, 1985. Courtesy of Yale Repertory Theatre Production of Two Trains Running at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago.

Production of Two Trains Running at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago.

Young August Kittel went to parochial school near his Hill District home on Bedford Avenue until his parents’ divorce. He, his mother, and his siblings moved from their historically black community to the Oakland neighborhood, which was primarily white. The constant bigotry of classmates led him to change high schools three times by the time he was fifteen, when he withdrew from formal school and began educating himself independently at Pittsburgh’s famed Carnegie Library. In 1962, at age 17, he enlisted in the Army but left after a year of service. After his father’s death in 1965, he took the name August Wilson to honor his mother.

Young August Kittel went to parochial school near his Hill District home on Bedford Avenue until his parents’ divorce. He, his mother, and his siblings moved from their historically black community to the Oakland neighborhood, which was primarily white. The constant bigotry of classmates led him to change high schools three times by the time he was fifteen, when he withdrew from formal school and began educating himself independently at Pittsburgh’s famed Carnegie Library. In 1962, at age 17, he enlisted in the Army but left after a year of service. After his father’s death in 1965, he took the name August Wilson to honor his mother. Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library c. 1935

Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library c. 1935 , was selected in 1982. Through the Conference, Wilson was introduced to the artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre, Lloyd Richards, who nurtured trailblazing playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the author of A Raisin in the Sun and the first African-American to have a play produced on Broadway. Richards helped shepherd the development of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and ended up directing Wilson’s first six plays on Broadway, including the 1987 Pulitzer Prize-winning Fences. Wilson earned his second Pulitzer in 1990 for The Piano Lesson.

, was selected in 1982. Through the Conference, Wilson was introduced to the artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre, Lloyd Richards, who nurtured trailblazing playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the author of A Raisin in the Sun and the first African-American to have a play produced on Broadway. Richards helped shepherd the development of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and ended up directing Wilson’s first six plays on Broadway, including the 1987 Pulitzer Prize-winning Fences. Wilson earned his second Pulitzer in 1990 for The Piano Lesson.

Perhaps the best-known Othello in the United States is the renowned actor Paul Robeson. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson had built an international reputation not only from his role in the musical Show Boat, but as an athlete and an attorney. Robeson had a commanding physical presence that suited the role perfectly, but his casting against the young British actress Peggy Ashcroft in 1930 was not without controversy. Technical issues like poor staging and difficult acoustics made performing difficult. But no one argued with the power of Robeson’s performance. Ivor Brown, the critic for The Observer, described Robeson as “… an oak…a superb giant of the woods for the great hurricane of tragedy to whisper through, then rage upon, then break.” Audiences at the premiere gave Robeson twenty curtain calls. But, given the societal segregation of the time, Robeson had detractors as well who criticized everything from his interpretation of the role to how he pronounced the words of Shakespeare’s text. Samantha Ellis writes:

Perhaps the best-known Othello in the United States is the renowned actor Paul Robeson. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson had built an international reputation not only from his role in the musical Show Boat, but as an athlete and an attorney. Robeson had a commanding physical presence that suited the role perfectly, but his casting against the young British actress Peggy Ashcroft in 1930 was not without controversy. Technical issues like poor staging and difficult acoustics made performing difficult. But no one argued with the power of Robeson’s performance. Ivor Brown, the critic for The Observer, described Robeson as “… an oak…a superb giant of the woods for the great hurricane of tragedy to whisper through, then rage upon, then break.” Audiences at the premiere gave Robeson twenty curtain calls. But, given the societal segregation of the time, Robeson had detractors as well who criticized everything from his interpretation of the role to how he pronounced the words of Shakespeare’s text. Samantha Ellis writes:

Thug Notes: Othello

Sex, booze, lies, and revenge–just another day on Cyprus! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Othello

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, commentary, drama, Othello, Shakespeare