Mya Gosling of Good Tickle Brain is a master of distilling Shakespeare into clever illustrations. Here’s her take on our friends in Messina.

Mya Gosling of Good Tickle Brain is a master of distilling Shakespeare into clever illustrations. Here’s her take on our friends in Messina.

Comments Off on All You Need to Know about Much Ado

Filed under AP Literature

In this sketch, comedian Rowan Atkinson (better known as Mr. Bean or the voice of Zazu, the majordomo bird in The Lion King) explains Elizabethan theater, including the roles of king and messenger and the importance of having a poison checker. Enjoy!

Comments Off on Mr. Bean Does Shakespeare

Filed under AP Literature, Honors IV

During the Elizabethan period of English history, theaters gained prominence and a greater role within the culture. Before this time, traveling actors were considered little better than thieves and vagrants. In 1572, acting was recognized as a lawful profession. Theater companies were required to be licensed. By 1574, theaters and companies were brought under the purview of the Master of Revels, who also had to approve all plays for performance.

During the Elizabethan period of English history, theaters gained prominence and a greater role within the culture. Before this time, traveling actors were considered little better than thieves and vagrants. In 1572, acting was recognized as a lawful profession. Theater companies were required to be licensed. By 1574, theaters and companies were brought under the purview of the Master of Revels, who also had to approve all plays for performance.

In order to receive a license, theater companies had to have the patronage of a nobleman. The troupe then took the name of its patron. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the company associated with Shakespeare, changed its name to The King’s Men after its patron, James VI of Scotland, succeeded Elizabeth to the English throne in 1603.

Acting troupes contained between ten and twenty members, divided between shareholding main members who were paid wages and divided some profits and contracted workers who could serve as extras onstage or as skilled workmen backstage. Apprentices to the companies were boys aged 14 and older. These apprentices received training in theater craft and played the parts of children and women. Once they completed their training, they could hire on with a troupe permanently or seek other employment. The playwright, a key and usually shareholding member of a troupe, would craft parts based on the strengths and capabilities of the men in the troupe.

Playwrights were expected to produce several works during a season. They assisted during rehearsals of their plays, making them directors of a sort. Troupes had to receive permission from the Master of Revels before a play could be offered in performance. Actors received copies of their lines with cues supplied. A summary of entrances, exits, and a general plot were posted backstage for reference during the performance, while a master kept a copy of the entire play, with additional notations about props, scene changes, and cues for musicians and stagehands.

Two types of playhouses existed during the Elizabethan era. Some were small, interior stages, usually in private buildings, which could be lit by candles for evening performances. Although anyone potentially could buy a ticket to a play at one of these theaters, only privileged groups usually did, leading these theaters to be labeled “private.” The more popular and well-known theaters were the large public theaters built on the outskirts of London (and therefore not subject to the city’s stringent laws). At least nine of these playhouses were active during the Elizabethan era, including The Theater, The Curtain, Newington Butts, The Rose (made famous by the film Shakespeare in Love), The Swan, The Fortune, The Red Bull, The Hope, and of course, The Globe, the playhouse most closely associated with Shakespeare. These theaters presented a series of plays in repertory during a season, with less-popular plays being canceled and newer ones being commissioned to take their places. Performances were held often, the exceptions being special holidays, certain days within the church calendar, and at times of plague or widespread sickness. Theaters indicated a performance was being held that day by flying a flag from the roof.

Public playhouses came in varying shapes (round, oval, octagonal, square), and all were open-air, necessitating afternoon performances. The central space, called the pit or yard, was used for general admission. Playgoers could usually get in for a penny to stand on the ground; these “groundlings” were largely uneducated, so playwrights would tailor portions of the play–usually bawdy jokes and physical slapstick–to suit them. Patrons could pay additional money to be seated in one of the galleries within the walls of the theater. Noble patrons were often granted seats in private boxes, some overlooking the stage itself. Playwrights catered to these patrons as well by inserting songs, poetry, and political and noble intrigue within the plot.

The stage itself was a raised platform four to six feet above ground level, extending into the pit area. To its rear was a multilevel facade with doors that served for entrances and exits with a balcony above. The balcony space could be used to represent a balcony (Romeo and Juliet), castle battlements (Macbeth), or other high places. To the rear was the discovery space, also called the “inner below” for what scholars assume was its location (under the balcony). This space was used to reveal or conceal objects and characters, like Polonius hiding behind the arras in Hamlet or Puck spying on the lovers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Because the stage lacked curtains, action was very nearly continuous. Scene and act breaks became more formalized in later years as theater spaces changed.

The stage itself was a raised platform four to six feet above ground level, extending into the pit area. To its rear was a multilevel facade with doors that served for entrances and exits with a balcony above. The balcony space could be used to represent a balcony (Romeo and Juliet), castle battlements (Macbeth), or other high places. To the rear was the discovery space, also called the “inner below” for what scholars assume was its location (under the balcony). This space was used to reveal or conceal objects and characters, like Polonius hiding behind the arras in Hamlet or Puck spying on the lovers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Because the stage lacked curtains, action was very nearly continuous. Scene and act breaks became more formalized in later years as theater spaces changed.

Shakespeare’s Globe was first built in 1599, with a reconstruction in 1614 after a fire set during a performance burned the original playhouse to the ground in a matter of hours. The rebuilt theater was closed, as all of the theaters were, by Oliver Cromwell during the English Protectorate (Puritan rule) in 1642 and torn down to accommodate more housing in 1644. In the 1980s, American actor Sam Wanamaker led an international effort to reconstruct The Globe Theatre near its original site in London, and the fully-operational theater reopened for performances in 1997, more than 350 years after the original theater was torn down. Click here for more information on the new Globe, which is pictured above. For a virtual tour of the theater space, click here.

Comments Off on Elizabethan Theater

Filed under AP Literature

Everybody dies.

P.S. They forgot one. In Act V, Scene 2 of Othello, Gratiano says about Desdemona, “I am glad thy father’s dead/Thy match was mortal to him, and pure grief/Shore his old thread in twain,” which suggests that, like Lady Montague, Brabantio died of a broken heart. This brings the death toll of Othello to five.

Concept by Cam Magee, design by Caitlin S. Griffin (who might possibly be this Caitlin Griffin, who is Education Programs Assistant for the Folger Shakespeare Library).

Comments Off on Shakespeare’s Tragedies

Filed under AP Literature

On November 1, 1604, Master of Revels Edmund Tilney notes that a play titled The Moor of Venice was performed at Whitehall Palace for King James I. In the four hundred-plus years since, Othello has become one of the best-known and regarded of Shakespeare’s plays. It has also presented a number of questions regarding its central character, Othello the Moor.

During the Elizabethan era, the word “Moor” could have meant several things. Scholar Ben Arogundade notes that “[‘Moor’] was first used to describe the natives of Mauretania — the region of North Africa which today corresponds to Morocco and Algeria. It was later applied to people of Berber and Arab origin, who conquered and ruled the Iberian Peninsula — the area now known as Spain and Portugal — for nearly eight centuries. From the Middle Ages onwards the Moors were commonly regarded as black Africans, and the word was used alongside the terms ‘negro,’ ‘Ethiopian’ and ‘Blackamoor’ as a racial identifier.

At the time of performance, London audiences would have been familiar with a man named Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri, who arrived in 1600 as an ambassador of the Sa’adian ruler of Morocco, Mulay Ahmed al-Mansur. England’s various alliances with the countries of North Africa familiarized the Elizabethan world with their traditions. Islamic and Muslim characters appeared in plays as early as Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great in 1587, and in more than sixty plays from the next ten years, characters described with words like “Moors,” “Saracens,” “Turks,” and “Persians” appeared, including several of Shakespeare’s own. So it is not without historical or literary precedent that some critics believe that the character of Othello is intended to be a North African man of Arab descent.

At the time of performance, London audiences would have been familiar with a man named Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri, who arrived in 1600 as an ambassador of the Sa’adian ruler of Morocco, Mulay Ahmed al-Mansur. England’s various alliances with the countries of North Africa familiarized the Elizabethan world with their traditions. Islamic and Muslim characters appeared in plays as early as Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great in 1587, and in more than sixty plays from the next ten years, characters described with words like “Moors,” “Saracens,” “Turks,” and “Persians” appeared, including several of Shakespeare’s own. So it is not without historical or literary precedent that some critics believe that the character of Othello is intended to be a North African man of Arab descent.

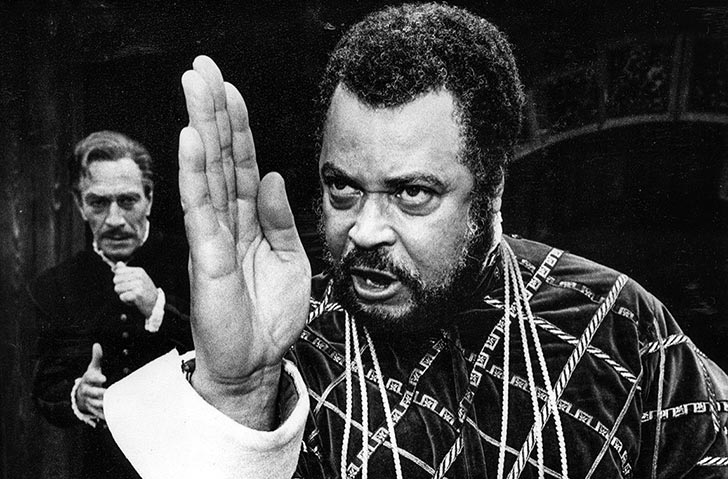

The far more common interpretation, however, is for Othello to be viewed as a sub-Saharan African with black features. It is this portrayal that is most commonly found in modern productions of the play. From Shakespeare’s time until the early 1800s, this meant that the actor tackling the role would have played it in blackface makeup.

It wasn’t until 1826 that Othello was finally played by a black performer: American actor Ira Aldridge. Aldridge emigrated to London at age 17 to pursue his acting career. But his groundbreaking performance wasn’t without criticism. The 1933 performance in Covent Garden was criticized by the paper The Anthenaeum because of the startling new reality of Ellen Tree, the white actress playing Desdemona, being manhandled by Aldridge. And although Aldridge became quite famous in London and abroad, it took nearly a hundred years before another black actor became attached to the role. According to writer Samantha Ellis, “In 1825, the pro-slavery lobby had closed [Aldridge’s] production and the Times‘s critic had written: ‘Owing to the shape of his lips it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English.’ No wonder it took almost a century for another black actor to brave the part.”

Perhaps the best-known Othello in the United States is the renowned actor Paul Robeson. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson had built an international reputation not only from his role in the musical Show Boat, but as an athlete and an attorney. Robeson had a commanding physical presence that suited the role perfectly, but his casting against the young British actress Peggy Ashcroft in 1930 was not without controversy. Technical issues like poor staging and difficult acoustics made performing difficult. But no one argued with the power of Robeson’s performance. Ivor Brown, the critic for The Observer, described Robeson as “… an oak…a superb giant of the woods for the great hurricane of tragedy to whisper through, then rage upon, then break.” Audiences at the premiere gave Robeson twenty curtain calls. But, given the societal segregation of the time, Robeson had detractors as well who criticized everything from his interpretation of the role to how he pronounced the words of Shakespeare’s text. Samantha Ellis writes:

Perhaps the best-known Othello in the United States is the renowned actor Paul Robeson. The son of an escaped slave, Robeson had built an international reputation not only from his role in the musical Show Boat, but as an athlete and an attorney. Robeson had a commanding physical presence that suited the role perfectly, but his casting against the young British actress Peggy Ashcroft in 1930 was not without controversy. Technical issues like poor staging and difficult acoustics made performing difficult. But no one argued with the power of Robeson’s performance. Ivor Brown, the critic for The Observer, described Robeson as “… an oak…a superb giant of the woods for the great hurricane of tragedy to whisper through, then rage upon, then break.” Audiences at the premiere gave Robeson twenty curtain calls. But, given the societal segregation of the time, Robeson had detractors as well who criticized everything from his interpretation of the role to how he pronounced the words of Shakespeare’s text. Samantha Ellis writes:

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, WA Darlington felt that Robeson was a “really memorable” Othello precisely because he was black: “By reason of his race Mr Robeson is able to surmount the difficulties which English actors generally find in the part.” While other Othellos had seemed illogically jealous, Robeson’s jealousy seemed real, because: “Mr Robeson…comes of a race whose characteristic is to keep control of its passions only to a point, and after that point to throw control to the winds.” It was a “fine” performance and “the much-debated question whether Shakespeare meant Othello to be a negro or an Arab can be left to the professors.” Baughan, in contrast, stated baldly: “I agree with Coleridge that Othello must not be conceived as a negro, but as a high and chivalrous Moorish chief.”

Only the Express‘s critic seemed to think the casting of a black actor was a historic event. He reported overhearing people saying “Why should a black actor be allowed to kiss a white actress?” and his review, subtitled “Coloured Audience in the Stalls,” concluded that Robeson had “triumphed as a negro Moor, black, swarthy, muscular, a real man of deep colour.”

Robeson himself enjoyed playing Othello, and it became his signature role for the remainder of his career. As Ellis notes, “For Robeson, it was more than just a part: it was, as he once said, ‘killing two birds with one stone. I’m acting and I’m talking for the negroes in the way only Shakespeare can.'”

Despite the positive reception of an African-American actor in the role, the Oscar-nominated 1965 production (the highest number for a Shakespeare film in history) starring Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Dame Maggie Smith as Desdemona reverted to type: The famous English actor played the role in makeup. This was the first cinematic Othello to be shot using color film, and Oliver was as meticulous about that as he was about developing the physical character through a deep voice and a special walk. He stated in an interview with Life magazine in 1964 that, “The whole [makeup] will be in the lips and the colour. I’ve been looking at Negroes lips every time I see them on the train or anywhere, and actually, their lips seems black or blueberry-coloured, really, rather than red. But of course the variations are enormous. I’ll just use a little tiny touch of lake and a lot more brown and a little mauve.”

Despite the positive reception of an African-American actor in the role, the Oscar-nominated 1965 production (the highest number for a Shakespeare film in history) starring Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Dame Maggie Smith as Desdemona reverted to type: The famous English actor played the role in makeup. This was the first cinematic Othello to be shot using color film, and Oliver was as meticulous about that as he was about developing the physical character through a deep voice and a special walk. He stated in an interview with Life magazine in 1964 that, “The whole [makeup] will be in the lips and the colour. I’ve been looking at Negroes lips every time I see them on the train or anywhere, and actually, their lips seems black or blueberry-coloured, really, rather than red. But of course the variations are enormous. I’ll just use a little tiny touch of lake and a lot more brown and a little mauve.”

But as well-received as the production was by the Oscar crowd, its release during the height of the Civil Rights Movement dampened its reception with audiences. Arongundade remarks that “…[Olivier’s] blackface portrayal troubled American critics when the film opened there in 1966…sensitivities about black identity were at their height, and many saw Olivier’s chosen aesthetic as outdated.”

Perhaps the pushback against the Olivier production opened the door for the now generally-accepted casting of an African-American actor in the role. Famous Othellos of the last several decades include theater luminaries like James Earl Jones, Oscar-nominated actor Laurence Fishburne in a stellar 1995 production starring Kenneth Branagh as Iago and French actress Irene Jacob as Desdemona, and young actor Mekhi Phifer in “O,” a contemporary version that transforms the military conflict into a basketball rivalry set in a high school. Other famous actors who have played Othello include Orson Welles, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Eamonn Walker in a 2001 TV movie co-starring Christopher Eccleston (best known as the ninth Doctor Who) as Iago, which transplants the action from Venice and Cyprus to a London police station.

Perhaps the pushback against the Olivier production opened the door for the now generally-accepted casting of an African-American actor in the role. Famous Othellos of the last several decades include theater luminaries like James Earl Jones, Oscar-nominated actor Laurence Fishburne in a stellar 1995 production starring Kenneth Branagh as Iago and French actress Irene Jacob as Desdemona, and young actor Mekhi Phifer in “O,” a contemporary version that transforms the military conflict into a basketball rivalry set in a high school. Other famous actors who have played Othello include Orson Welles, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Eamonn Walker in a 2001 TV movie co-starring Christopher Eccleston (best known as the ninth Doctor Who) as Iago, which transplants the action from Venice and Cyprus to a London police station.

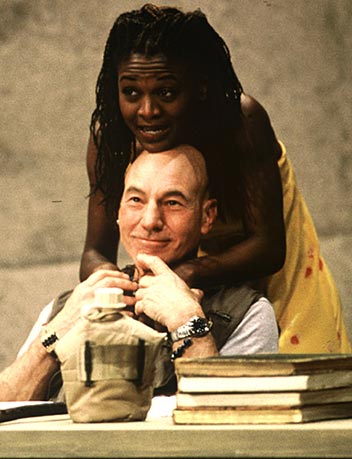

Modern theater companies wishing to explore the themes of Othello in new ways have explored variant casting. A 1997 production of the play in Baltimore starred Patrick Stewart as Othello, the lone white actor in a racially-flipped cast in which every other actor was African-American. Stewart, pictured here with Patrice Johnson as Desdemona, explained, “One of my hopes for this production is that it will continue to say what a conventional production of Othello would say about racism and prejudice… To replace the black outsider with a white man in a black society will, I hope, encourage a much broader view of the fundamentals of racism.” A review in the Baltimore Sun said, “It is a tribute to the concept as well as Stewart’s performance that the initial awkwardness falls away as early as his second scene…Stewart, who possesses a calm assuredness at the start of the play, lets the theater’s predominantly white audience experience how completely foreign Othello must have felt in a society where he was viewed as the outsider.”

Speaking of foreign: A German production at the Deutsches Theatre in 2001 pushed the boundaries of the character by not only casting a white actor as Othello, but a female one. This more avant-garde production starring actress Susanne Wolff sees Wolff utter her lines in varying costumes progressing from a simple black-and-white shirt and pants ensemble to—believe it or not—a gorilla suit intended to show Othello’s shift from loving partner to a more animalistic creature bent on vengeance. Blogger/reviewer Andrew Haydon says about the production, “Okay, there are two headlines to choose from here: 1) I’ve just seen the best production of Othello I’ve ever seen. 2) I’ve just seen a production of Othello in which Othello is played by a white woman in a gorilla costume. My job, then, is to explain how (2) manages to be (1).”

Speaking of foreign: A German production at the Deutsches Theatre in 2001 pushed the boundaries of the character by not only casting a white actor as Othello, but a female one. This more avant-garde production starring actress Susanne Wolff sees Wolff utter her lines in varying costumes progressing from a simple black-and-white shirt and pants ensemble to—believe it or not—a gorilla suit intended to show Othello’s shift from loving partner to a more animalistic creature bent on vengeance. Blogger/reviewer Andrew Haydon says about the production, “Okay, there are two headlines to choose from here: 1) I’ve just seen the best production of Othello I’ve ever seen. 2) I’ve just seen a production of Othello in which Othello is played by a white woman in a gorilla costume. My job, then, is to explain how (2) manages to be (1).”

Sources:

Ben Arungodade, “What Was Othello’s Race?” and “The 18 Most Memorable Othello Actors Performances”

Baltimore Sun review of Sir Patrick Stewart Othello

Jerry Brotton, “Is This the Real Model for Othello?”

Samantha Ellis, “Paul Robeson in Othello, Savoy Theatre, 1930”

Emily Anne Gibson, “The Face of Othello”

Andrew Haydon, “Othello – Deutsches Theatre”

Othello Relating His Adventures to Desdemona by Carl Ludwig Friedrich Becker, 1880.

Comments Off on Many Faces of Othello

Filed under AP Literature

To access a copy of Othello on your device, try the links provided on Canvas.

To access a copy of Othello on your device, try the links provided on Canvas.

Download or listen to a streaming audio version of the play at Librivox.

A PDF of the play from the Folger Library may be found here.

The full text of the play may be read online here.

Scenes plus notes may be found here.

If you get truly stuck, the “No Fear Shakespeare” version from SparkNotes, with side-by-side modern English translation, is available here. Use this only if you’re completely lost. Trust yourself first!

The Orange County Library System has tons of Shakespeare resources, including the 1995 Fishburne/Branagh version in both DVD and online streaming formats, the 1965 Olivier on DVD, and the 2001 BBC TV production on DVD.

Use video resources to enhance your reading through YouTube. Shakespeare in performance is very different from tackling the text alone.

Comments Off on Othello – Text Sources

Filed under AP Literature

Copy each statement and indicate whether you agree or disagree.

Copy each statement and indicate whether you agree or disagree.

It can sometimes be difficult to determine the honesty of a friend.

When a person’s reputation has been tainted, it can never be restored.

Parents know what is best for their children.

A person’s love can be gained through material wealth.

Racial and age differences in a marriage are easily overcome.

Secondhand information is reliable.

Military heroes shouldn’t get distracted with things like love. It makes them weak.

Reputation is the most important thing in the world.

Imagination can be worse than reality.

Physical violence is the best kind of revenge.

If someone deceives me, it’s all his fault.

Best friends make the worst enemies.

No person can avoid being intensely jealous at some point.

Once you have established trust with someone, you can trust their counsel.

Of the emotions of anger, resentment, jealousy, or loneliness, jealousy hurts the most.

After you have made your selections, choose three of the statements and explain briefly what made you choose whether you agreed or disagreed with the statement. (You may do this on the back of the paper.)

Comments Off on Othello Anticipation Guide

Filed under AP Literature

Lovers, asses, and fools—you know, everything you become when you fall in love. Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Filed under AP Literature

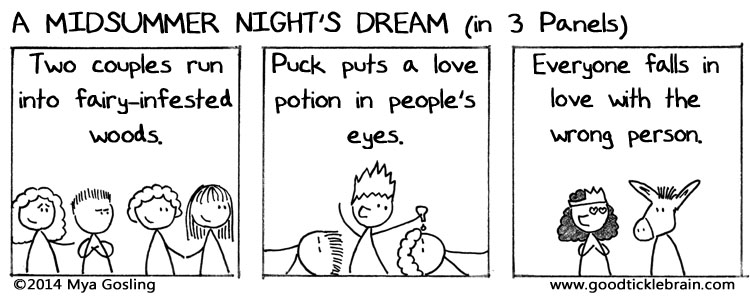

Artist Mya Gosling’s Peace, Good Tickle Brain online is a treasure trove of Shakespeare-related fun, including three-panel cartoons for a number of the plays. Here’s her cartoon for A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

Her version of Midsummer with Star Wars action figures is a hoot. What happens when Luke, Leia, Han, Chewie, Darth Vader, C-3PO, Yoda, and even Emperor Palpatine become the “Rude Galacticals”? It starts here.

Comments Off on Midsummer Simplified

Filed under AP Literature

Thug Notes: Othello

Sex, booze, lies, and revenge–just another day on Cyprus! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Othello

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, commentary, drama, Othello, Shakespeare