“Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun.’ We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.”

From Dust Tracks on a Road

Although Zora Neale Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama on January 7, 1891, she moved to Eatonville, Florida when she was a toddler and claimed that as her hometown. Eatonville, the first black-incorporated town in the United States, served as the backdrop for her most famous work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, in addition to providing a rich vein of African-American folklore that resounds throughout her writing. Trained as a cultural anthropologist, Hurston sought to incorporate the black culture and dialect that she knew best into her writing. Her positive outlook on black culture as it was created friction between Hurston and other luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance movement. After a few decades of literary success, Hurston fell into obscurity. Her works went out of print. It wasn’t until novelist Alice Walker, who had read Their Eyes Were Watching God and who became a passionate advocate of her work, published the essay “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” in a 1975 issue of Ms. Magazine that scholars renewed their focus on the Hurston, her amazing life story, and her contribution to American literature. Their Eyes Were Watching God is now one of the most widely-taught and best-known of African-American novels. Hurston died in Ft. Pierce, FL on January 28, 1960.

Hurston’s Perspective

What strikes the contemporary reader is that Hurston was deeply passionate about the people whose dreams and desires, whose traumas and foibles she describes with such élan, and that she loved the fictional language in which she cloaks their tales; hers is not the urgency of the essayist or the columnist, intent upon reducing human complexity to a sociological or political point. Above all else, Hurston is concerned to register a distinct sense of space—an African-American cultural space. The Hurston voice of these stories is never in a hurry or a rush, pausing over—indeed, luxuriating in—the nuances of speech or the timbre of voice that give a storyteller her or his distinctiveness.

—Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Sieglinde Lemke,

Introduction to Zora Neale Hurston: The Complete StoriesIn the twenties, thirties, and forties, there were tremendous pressures on black writers. Militant organizations, like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, expected them to be “race” people, defending black people, protesting against racism and oppression; while the advocates of the genteel school of literature wanted black writers to create respectable characters that would be “a credit to the race.” Many black writers chafed under these restrictions, including Hurston, who chose to write about the positive side of black experience and to ignore the brutal side. She saw black lives as psychologically integral—not humiliated half-lives, stunted by the effects of racism and poverty. She simply could not depict blacks as defeated, humiliated, degraded, or victimized, because she did not experience black people or herself that way.

Mary Helen Washington, “Zora Neale Hurston: A Woman Half in Shadow”

“I tried … not to pander to the folks who expect a clown and a villain in every Negro,” Hurston said of Their Eyes Were Watching God. “Neither did I want to pander to those ‘race’ people among us who see nothing but perfection in all of us.”

“I tried … not to pander to the folks who expect a clown and a villain in every Negro,” Hurston said of Their Eyes Were Watching God. “Neither did I want to pander to those ‘race’ people among us who see nothing but perfection in all of us.”

Hurston’s Language

Reading Their Eyes Were Watching God for perhaps the eleventh time, I am still amazed that Hurston wrote it in seven weeks; that it speaks to me as no novel, past or present, has ever done; and that the language of the characters, that “comical nigger ‘dialect’” that has been laughed at, denied, ignored, or “improved” so that white folks and educated black folks can understand it, is simply beautiful. There is enough self-love in that one book—love of community, culture, traditions—to restore a world. Or create a new one.

Alice Walker, “On Refusing to be Humbled By Second Place in a Contest You Did Not Design: A Tradition by Now”

Hurston Resources

The PBS program Do You Speak American? includes an excellent essay on African-American women writers including Hurston, Alice Walker, and Nobel prizewinner Toni Morrison. Hurston’s use of dialect is discussed in detail. The essay also includes links to sounds clips and other info:

www.pbs.org/speak/seatosea/powerprose/hurston

The idea that there are proscribed ways for people of varied races to speak still exists these days. In her podcast “Sounding Black,” produced for Studio 360, performer Sarah Jones discusses “blaccents” and their impact on communication and the 2008 presidential election.

www.studio360.org/episodes/2009/10/16/segments/142665

“Lord of the Flies is a very serious book which has to be introduced seriously. The danger of such an introduction is that it may suggest that the book is stodgy. It is not. It is written with taste and liveliness, the talk is natural, the descriptions of scenery enchanting. It is certainly not a comforting book. But it may help a few grownups to be less complacent and more compassionate, to support Ralph, to respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart. At the present moment (if I may speak personally), it is respect for Piggythat seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders.”

“Lord of the Flies is a very serious book which has to be introduced seriously. The danger of such an introduction is that it may suggest that the book is stodgy. It is not. It is written with taste and liveliness, the talk is natural, the descriptions of scenery enchanting. It is certainly not a comforting book. But it may help a few grownups to be less complacent and more compassionate, to support Ralph, to respect Piggy, control Jack, and lighten a little the darkness of man’s heart. At the present moment (if I may speak personally), it is respect for Piggythat seems needed most. I do not find it in our leaders.” “The South-Sea island setting suggests everyone’s fantasy of lotus-eating escape or refuge from troubles and care. But for Golding this is the sheerest fantasy: there is no escape from the agony of being human, no possibility of erecting utopian political systems where all will go well. Man’s inescapable depravity makes sure “it’s no-go” on Golding’s island just as it does on the various islands visited by Gulliver in Swift’s excoriating examination of the realities of the human condition.”

“The South-Sea island setting suggests everyone’s fantasy of lotus-eating escape or refuge from troubles and care. But for Golding this is the sheerest fantasy: there is no escape from the agony of being human, no possibility of erecting utopian political systems where all will go well. Man’s inescapable depravity makes sure “it’s no-go” on Golding’s island just as it does on the various islands visited by Gulliver in Swift’s excoriating examination of the realities of the human condition.”

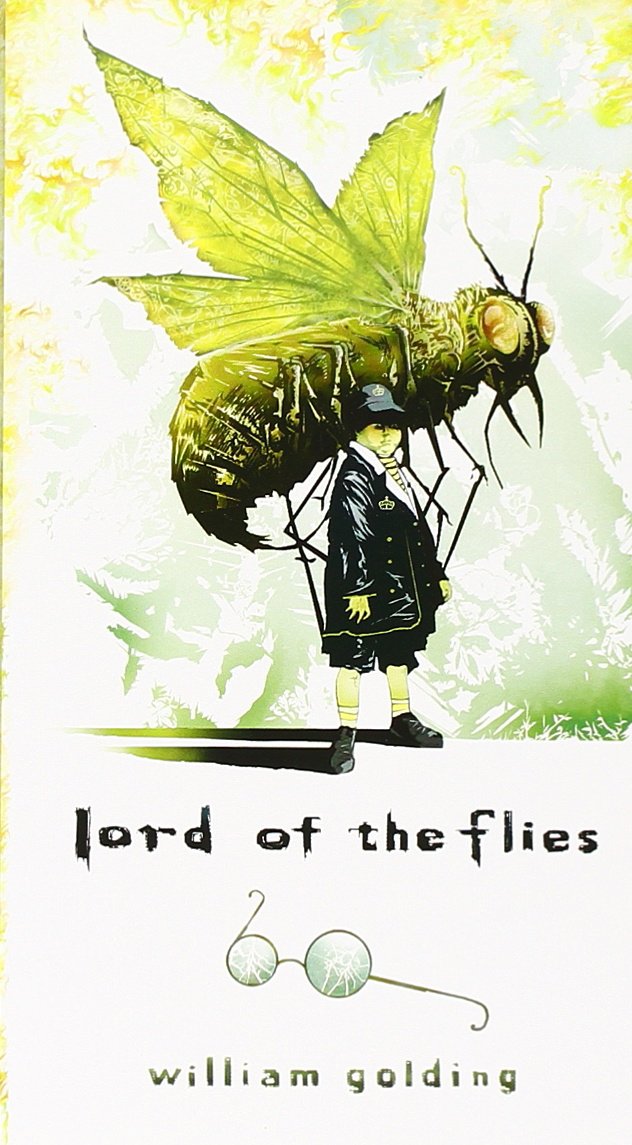

Christopher King, the art director for the American publishing house Melville House, explored some of the design choices for Lord of the Flies in

Christopher King, the art director for the American publishing house Melville House, explored some of the design choices for Lord of the Flies in

In the end, the judges unanimously selected the mixed media work of 15-year-old Sarah Baxter as the contest winner. An interview with Sarah was published in

In the end, the judges unanimously selected the mixed media work of 15-year-old Sarah Baxter as the contest winner. An interview with Sarah was published in

Thug Notes: Lord of the Flies

Life in this hood is savage, yo! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Lord of the Flies

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, commentary, LOTF