The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

–William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

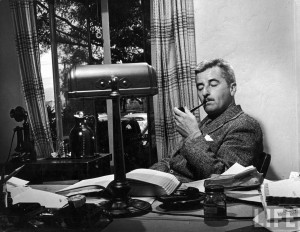

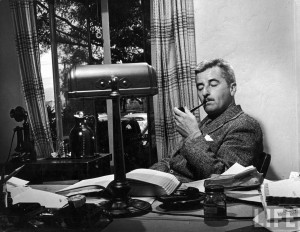

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Faulkner was born in Mississippi in 1897. He began writing as a young man. When World War I broke out, Faulkner attempted to enlist in the Army, but his age and height (he was only 5’5-1/2″) kept him out. Undaunted, Faulkner went to Canada to enlist in the British Royal Flying Corps. Despite never actually serving, he was fond of wearing his uniform and carrying the swagger stick he’d been issued. Soon after, he moved to New Orleans to begin his writing career. His first novel, Soldier’s Pay, was published in 1925. Apart from this brief period in New Orleans, occasional stints as a Hollywood screenwriter in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and as a writer in residence at the University of Virginia in the 1950s, he primarily lived and worked in his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi. He once remarked, “I discovered my own little postage stamp of native soil was worth writing about and that I would never live long enough to exhaust it.”

He was right. His interwoven collection of short stories and novels focused on his own back yard. Lafayette County became the fabled, fictional Yoknapatawpha County, whose families, history, and tales reflected both the high-minded ideals of the mythical South and the tangled, messy actualities of a region marked by pride, poverty, social status, and segregation.

Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s home, is now owned and operated as a museum by the University of Mississippi. The house is preserved much as it was in Faulkner’s day. His Underwood typewriter sits ready on a desk, while riding boots rest on the floor next to a chair. A full outline and story notes for one of his last published works, A Fable, are penciled across the walls of his study. Faulkner’s connection to this house was legendary. One story goes that during one of Faulkner’s screenwriting jobs, the studio put him in an office and left him to work. After some time passed without much output, Faulkner said he thought he could write better from home, and the studio agreed. More time passed without any production, so the studio sent someone to Faulkner’s temporary California apartment—and he wasn’t there. When he asked to write from home, he meant Rowan Oak. They called and sure enough, Faulkner was in Mississippi, proving what he wrote for The Paris Review in 1956: “An artist is a creature driven by demons. He don’t know why they choose him and he’s usually too busy to wonder why. He is completely amoral in that he will rob, borrow, beg, or steal from anybody and everybody to get the work done.”

Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s home, is now owned and operated as a museum by the University of Mississippi. The house is preserved much as it was in Faulkner’s day. His Underwood typewriter sits ready on a desk, while riding boots rest on the floor next to a chair. A full outline and story notes for one of his last published works, A Fable, are penciled across the walls of his study. Faulkner’s connection to this house was legendary. One story goes that during one of Faulkner’s screenwriting jobs, the studio put him in an office and left him to work. After some time passed without much output, Faulkner said he thought he could write better from home, and the studio agreed. More time passed without any production, so the studio sent someone to Faulkner’s temporary California apartment—and he wasn’t there. When he asked to write from home, he meant Rowan Oak. They called and sure enough, Faulkner was in Mississippi, proving what he wrote for The Paris Review in 1956: “An artist is a creature driven by demons. He don’t know why they choose him and he’s usually too busy to wonder why. He is completely amoral in that he will rob, borrow, beg, or steal from anybody and everybody to get the work done.”

Faulkner’s life was marked by excesses—his concentration on his work, his home, his alcohol consumption (he did not drink while writing but often binged afterward). He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in both 1955 and posthumously in 1963, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for his body of work in 1949. In his acceptance speech he remarked, “I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work—a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust.” Hear a clip of his acceptance speech here.

Faulkner’s techniques, including his exploration of stream-of-consciousness writing, his invented verbiage, and his convoluted timelines, have earned him a permanent place near the top of the Southern literary tradition. Flannery O’Connor, another celebrated Southern author, stated that “the presence alone of Faulkner in our midst makes a great difference in what the writer can and cannot permit himself to do. Nobody wants his mule and wagon stalled on the same track the Dixie Limited is roaring down.”

For all kinds of great Faulkner resources, visit William Faulkner on the Web, hosted by the University of Mississippi.

“William Faulkner’s Hollywood Odyssey,” by John Maroney about Faulkner’s screenwriting days, was published in Garden and Gun magazine in 2014. Read it here.

Now that we have completed the first semester, it is time to reflect on your performance as a student of AP English. For this assignment, you will need to review the items in your portfolio and the scores you received on the semester mock exam.

Now that we have completed the first semester, it is time to reflect on your performance as a student of AP English. For this assignment, you will need to review the items in your portfolio and the scores you received on the semester mock exam.

Norwegian-born Henrik Ibsen’s classic play about the struggle between independence and security still resonates with readers and audience members today. Often hailed as an early feminist work, the story of Nora and Torvald rises above simple gender issues to ask the bigger question: To what extent have we sacrificed our selves for the sake of social customs and to protect what we think is love? Nora’s struggle and ultimate realizations about her life invite all of us to examine our own lives and find the many ways we have made ourselves dolls and playthings in the hands of forces we believe to be beyond our control.

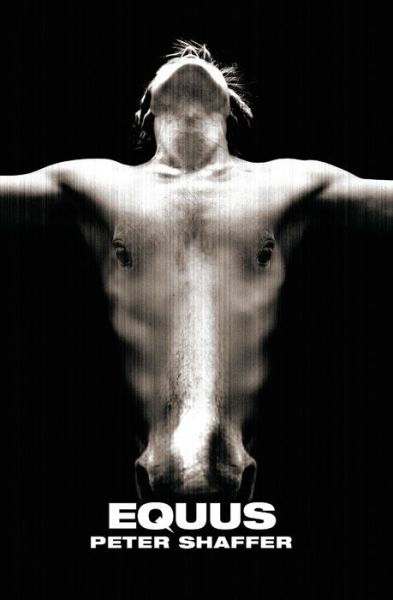

Norwegian-born Henrik Ibsen’s classic play about the struggle between independence and security still resonates with readers and audience members today. Often hailed as an early feminist work, the story of Nora and Torvald rises above simple gender issues to ask the bigger question: To what extent have we sacrificed our selves for the sake of social customs and to protect what we think is love? Nora’s struggle and ultimate realizations about her life invite all of us to examine our own lives and find the many ways we have made ourselves dolls and playthings in the hands of forces we believe to be beyond our control. An explosive play that took critics and audiences by storm, Equus is Peter Shaffer’s exploration of the way modern society has destroyed our ability to feel passion. Alan Strang is a disturbed youth whose dangerous obsession with horses leads him to commit an unspeakable act of violence. As psychiatrist Martin Dysart struggles to understand the motivation for Alan’s brutality, he is increasingly drawn into Alan’s web and eventually forced to question his own sanity. Equus is a timeless classic and a cornerstone of contemporary drama that delves into the darkest recesses of human existence.

An explosive play that took critics and audiences by storm, Equus is Peter Shaffer’s exploration of the way modern society has destroyed our ability to feel passion. Alan Strang is a disturbed youth whose dangerous obsession with horses leads him to commit an unspeakable act of violence. As psychiatrist Martin Dysart struggles to understand the motivation for Alan’s brutality, he is increasingly drawn into Alan’s web and eventually forced to question his own sanity. Equus is a timeless classic and a cornerstone of contemporary drama that delves into the darkest recesses of human existence. From August Wilson, author of the ten-part “Pittsburgh Cycle” of plays dramatizing the African-American experience in the twentieth century, comes this powerful, stunning work that won the 1987 Tony Award for Best Play and the Pulitzer Prize. The protagonist of Fences, Troy Maxson, is a strong man, a hard man. He has had to be to survive. Troy has gone through life in an America where to be proud and black is to face pressures that could crush a man, body and soul. But the 1950s are yielding to the new spirit of liberation in the 1960s, a spirit that is changing the world Troy has learned to deal with the only way he can, a spirit that is making him a stranger, angry and afraid, in a world he never knew and to a wife and son he understands less and less.

From August Wilson, author of the ten-part “Pittsburgh Cycle” of plays dramatizing the African-American experience in the twentieth century, comes this powerful, stunning work that won the 1987 Tony Award for Best Play and the Pulitzer Prize. The protagonist of Fences, Troy Maxson, is a strong man, a hard man. He has had to be to survive. Troy has gone through life in an America where to be proud and black is to face pressures that could crush a man, body and soul. But the 1950s are yielding to the new spirit of liberation in the 1960s, a spirit that is changing the world Troy has learned to deal with the only way he can, a spirit that is making him a stranger, angry and afraid, in a world he never knew and to a wife and son he understands less and less. Set on Chicago’s South Side, the plot revolves around the divergent dreams and conflicts within three generations of the Younger family: son Walter Lee, his wife Ruth, his sister Beneatha, his son Travis and matriarch Lena, called Mama. When her deceased husband’s insurance money comes through, Mama dreams of moving to a new home and a better neighborhood in Chicago. Walter Lee, a chauffeur, has other plans, however: buying a liquor store and being his own man. Beneatha dreams of medical school. The tensions and prejudice they face form this seminal American drama. Sacrifice, trust and love among the Younger family and their heroic struggle to retain dignity in a harsh and changing world is a searing and timeless document of hope and inspiration.

Set on Chicago’s South Side, the plot revolves around the divergent dreams and conflicts within three generations of the Younger family: son Walter Lee, his wife Ruth, his sister Beneatha, his son Travis and matriarch Lena, called Mama. When her deceased husband’s insurance money comes through, Mama dreams of moving to a new home and a better neighborhood in Chicago. Walter Lee, a chauffeur, has other plans, however: buying a liquor store and being his own man. Beneatha dreams of medical school. The tensions and prejudice they face form this seminal American drama. Sacrifice, trust and love among the Younger family and their heroic struggle to retain dignity in a harsh and changing world is a searing and timeless document of hope and inspiration.

Foldables (as anyone who’s ever has Mrs. Parm for a class would know) can prove to be a very helpful study aid. We’ll be using a simple foldable to collect textual support for your seminar on Light in August.

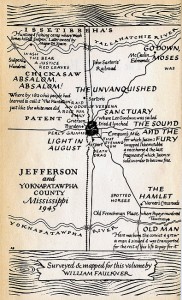

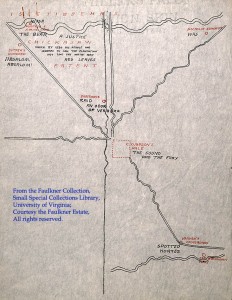

Foldables (as anyone who’s ever has Mrs. Parm for a class would know) can prove to be a very helpful study aid. We’ll be using a simple foldable to collect textual support for your seminar on Light in August. Much like English novelist Thomas Hardy, whose “Wessex” is a fictional amalgam of real locations, Faulkner based Yoknapatawpha County on very real places. Faulkner lived for most of his life in Oxford, Mississippi. In Faulkner’s work, Oxford becomes the town of Jefferson, while the real Jefferson County is named “Yoknapatawpha” after the old Chickasaw word for the Yocona River south of town. The county is located in north central Mississippi not far from the Tennessee border. This 1947 map indicates the primary locations of several of Faulkner’s major works, including not only Light in August but also his masterworks Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury.

Much like English novelist Thomas Hardy, whose “Wessex” is a fictional amalgam of real locations, Faulkner based Yoknapatawpha County on very real places. Faulkner lived for most of his life in Oxford, Mississippi. In Faulkner’s work, Oxford becomes the town of Jefferson, while the real Jefferson County is named “Yoknapatawpha” after the old Chickasaw word for the Yocona River south of town. The county is located in north central Mississippi not far from the Tennessee border. This 1947 map indicates the primary locations of several of Faulkner’s major works, including not only Light in August but also his masterworks Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury.

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner is one of the best-known of Southern writers, if not the preeminent one. His rich and evocative writing style is unparalleled and very different from many of his contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway. Where Hemingway is spare, direct, and laconic, Faulkner is lush, meandering, and protracted. One famous Faulkner sentence, located in the middle of Absalom, Absalom!, runs for 1,288 words. In that sense, Faulkner’s writing is much like the South he loved and sought to preserve on the page: a complicated, tangled mixture of the lyrical and the everyday.

Thug Notes: Lit Circles Novels

Sparky Sweets, Ph. D., is a big fan of messed up dystopias, y’all! Salty language and adult themes ahead. Proceed with caution.

And because Dr. Sweets hasn’t gotten around to it yet, here’s the Shmoop review of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest:

Comments Off on Thug Notes: Lit Circles Novels

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as 1984, analysis, Brave New World, commentary, lit circles, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, The Handmaid's Tale