“Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun.’ We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.”

From Dust Tracks on a Road

Although Zora Neale Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama on January 7, 1891, she moved to Eatonville, Florida when she was a toddler and claimed that as her hometown. Eatonville, the first black-incorporated town in the United States, served as the backdrop for her most famous work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, in addition to providing a rich vein of African-American folklore that resounds throughout her writing. Trained as a cultural anthropologist, Hurston sought to incorporate the black culture and dialect that she knew best into her writing. Her positive outlook on black culture as it was created friction between Hurston and other luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance movement. After a few decades of literary success, Hurston fell into obscurity. Her works went out of print. It wasn’t until novelist Alice Walker, who had read Their Eyes Were Watching God and who became a passionate advocate of her work, published the essay “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” in a 1975 issue of Ms. Magazine that scholars renewed their focus on the Hurston, her amazing life story, and her contribution to American literature. Their Eyes Were Watching God is now one of the most widely-taught and best-known of African-American novels. Hurston died in Ft. Pierce, FL on January 28, 1960.

Hurston’s Perspective

What strikes the contemporary reader is that Hurston was deeply passionate about the people whose dreams and desires, whose traumas and foibles she describes with such élan, and that she loved the fictional language in which she cloaks their tales; hers is not the urgency of the essayist or the columnist, intent upon reducing human complexity to a sociological or political point. Above all else, Hurston is concerned to register a distinct sense of space—an African-American cultural space. The Hurston voice of these stories is never in a hurry or a rush, pausing over—indeed, luxuriating in—the nuances of speech or the timbre of voice that give a storyteller her or his distinctiveness.

—Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Sieglinde Lemke,

Introduction to Zora Neale Hurston: The Complete StoriesIn the twenties, thirties, and forties, there were tremendous pressures on black writers. Militant organizations, like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, expected them to be “race” people, defending black people, protesting against racism and oppression; while the advocates of the genteel school of literature wanted black writers to create respectable characters that would be “a credit to the race.” Many black writers chafed under these restrictions, including Hurston, who chose to write about the positive side of black experience and to ignore the brutal side. She saw black lives as psychologically integral—not humiliated half-lives, stunted by the effects of racism and poverty. She simply could not depict blacks as defeated, humiliated, degraded, or victimized, because she did not experience black people or herself that way.

Mary Helen Washington, “Zora Neale Hurston: A Woman Half in Shadow”

“I tried … not to pander to the folks who expect a clown and a villain in every Negro,” Hurston said of Their Eyes Were Watching God. “Neither did I want to pander to those ‘race’ people among us who see nothing but perfection in all of us.”

“I tried … not to pander to the folks who expect a clown and a villain in every Negro,” Hurston said of Their Eyes Were Watching God. “Neither did I want to pander to those ‘race’ people among us who see nothing but perfection in all of us.”

Hurston’s Language

Reading Their Eyes Were Watching God for perhaps the eleventh time, I am still amazed that Hurston wrote it in seven weeks; that it speaks to me as no novel, past or present, has ever done; and that the language of the characters, that “comical nigger ‘dialect’” that has been laughed at, denied, ignored, or “improved” so that white folks and educated black folks can understand it, is simply beautiful. There is enough self-love in that one book—love of community, culture, traditions—to restore a world. Or create a new one.

Alice Walker, “On Refusing to be Humbled By Second Place in a Contest You Did Not Design: A Tradition by Now”

Hurston Resources

The PBS program Do You Speak American? includes an excellent essay on African-American women writers including Hurston, Alice Walker, and Nobel prizewinner Toni Morrison. Hurston’s use of dialect is discussed in detail. The essay also includes links to sounds clips and other info:

www.pbs.org/speak/seatosea/powerprose/hurston

The idea that there are proscribed ways for people of varied races to speak still exists these days. In her podcast “Sounding Black,” produced for Studio 360, performer Sarah Jones discusses “blaccents” and their impact on communication and the 2008 presidential election.

www.studio360.org/episodes/2009/10/16/segments/142665

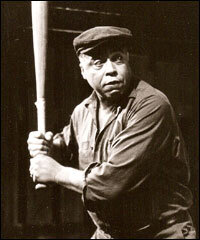

Mary Alice, James Earl Jones and Courtney Vance in Fences at Yale Repertory Theatre. William B. Carter, 1985. Courtesy of Yale Repertory Theatre

Mary Alice, James Earl Jones and Courtney Vance in Fences at Yale Repertory Theatre. William B. Carter, 1985. Courtesy of Yale Repertory Theatre Production of Two Trains Running at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago.

Production of Two Trains Running at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago.

Young August Kittel went to parochial school near his Hill District home on Bedford Avenue until his parents’ divorce. He, his mother, and his siblings moved from their historically black community to the Oakland neighborhood, which was primarily white. The constant bigotry of classmates led him to change high schools three times by the time he was fifteen, when he withdrew from formal school and began educating himself independently at Pittsburgh’s famed Carnegie Library. In 1962, at age 17, he enlisted in the Army but left after a year of service. After his father’s death in 1965, he took the name August Wilson to honor his mother.

Young August Kittel went to parochial school near his Hill District home on Bedford Avenue until his parents’ divorce. He, his mother, and his siblings moved from their historically black community to the Oakland neighborhood, which was primarily white. The constant bigotry of classmates led him to change high schools three times by the time he was fifteen, when he withdrew from formal school and began educating himself independently at Pittsburgh’s famed Carnegie Library. In 1962, at age 17, he enlisted in the Army but left after a year of service. After his father’s death in 1965, he took the name August Wilson to honor his mother. Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library c. 1935

Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library c. 1935 , was selected in 1982. Through the Conference, Wilson was introduced to the artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre, Lloyd Richards, who nurtured trailblazing playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the author of A Raisin in the Sun and the first African-American to have a play produced on Broadway. Richards helped shepherd the development of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and ended up directing Wilson’s first six plays on Broadway, including the 1987 Pulitzer Prize-winning Fences. Wilson earned his second Pulitzer in 1990 for The Piano Lesson.

, was selected in 1982. Through the Conference, Wilson was introduced to the artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre, Lloyd Richards, who nurtured trailblazing playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the author of A Raisin in the Sun and the first African-American to have a play produced on Broadway. Richards helped shepherd the development of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and ended up directing Wilson’s first six plays on Broadway, including the 1987 Pulitzer Prize-winning Fences. Wilson earned his second Pulitzer in 1990 for The Piano Lesson.

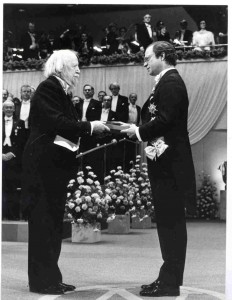

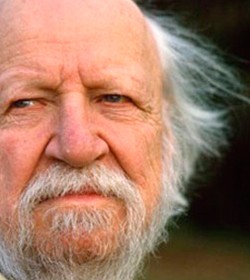

In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

In 1945, Golding resumed his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth’s School and began writing again. Some of his reviews and essays were published, but he found no publisher for the novels he had written. In spite of this, Golding persisted. He concluded that since he would probably never be published, he would simply write for his own satisfaction. One night after reading a bedtime story to his children, he spoke with his wife about his true desire, to write a book about what people are really like. Boys’ adventure books such as Coral Island and Treasure Island weren’t believable, and he wanted to trace the darkness that he witnessed as being part of every human being. The result was Lord of the Flies, published in 1954 when Golding was 43. Lord of the Flies sold well when first published;however, it sold fewer than 3,000 copies in the United States and soon went out of print. Later, the novel found and retained an influential audience and eventually became a favorite of college students, rivaled only by J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Later Golding published The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), and Free Fall (1959).

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

When looking at Golding’s philosophical attitude about Lord of the Flies, one interpretation is that each individual must acknowledge his connection to all people. Humanity’s problems stem from lack of awareness of this truth. People remain trapped inside themselves, too self-absorbed to look at the world around them. Only if people are able to see themselves as part of the whole, not as islands, will they find salvation. Humans must somehow find a way to connect with outer reality. Golding believes that humans’ intelligence will help them to make this necessary connection: one cannot change basic human nature, but can recognize and understand it. In so doing, individuals can willfully choose to suppress the savagery beneath their humanity.

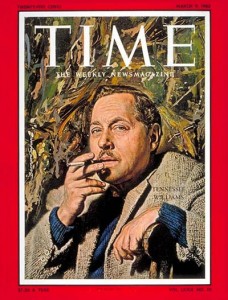

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

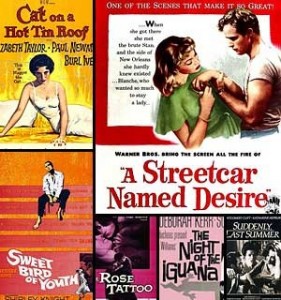

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

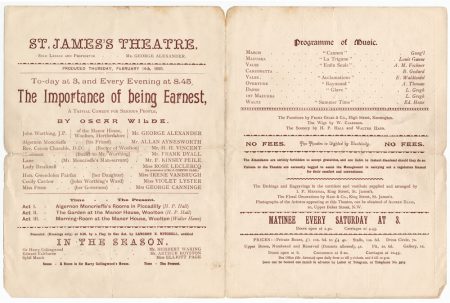

Oscar Wilde, the Irish playwright who became the darling of British high society, is probably the best-known and most-quoted satirist of the late 19th century. Born in Dublin, Ireland in 1864, Wilde became a well-known lecturer, essayist, and playwright who enjoyed near-universal popularity until the shocking trial that ended his literary career and, not long after, his life.

Oscar Wilde, the Irish playwright who became the darling of British high society, is probably the best-known and most-quoted satirist of the late 19th century. Born in Dublin, Ireland in 1864, Wilde became a well-known lecturer, essayist, and playwright who enjoyed near-universal popularity until the shocking trial that ended his literary career and, not long after, his life. The next year, Wilde’s first play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, made its debut to great acclaim. Playwriting became Wilde’s preferred literary style. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed in short order by A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and both An Ideal Husband and his most famous play, The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Each of these works skewered the pretensions of British high society through clever wordplay and Wilde’s satirical wit.

The next year, Wilde’s first play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, made its debut to great acclaim. Playwriting became Wilde’s preferred literary style. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed in short order by A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and both An Ideal Husband and his most famous play, The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Each of these works skewered the pretensions of British high society through clever wordplay and Wilde’s satirical wit.

Shakespeare: Let It All Out

Some of my favorite comments you wrote about Shakespeare:

“I once got knocked out by being slammed on my head. Compared to Shakespeare, getting knocked out is fun. At least it is quicker.”

“I think Shakespeare is pretty freaking cool, even though sometimes it can be hella hard to translate.”

“His works are a vile thing, equivalent to castration and fingernail-bamboo torture.”

“I bite my thumb at Shakespeare.”

“In every play he kills almost everyone. IN EVERY PLAY. I can’t. I can’t even.”

“Let’s begin with the spelling of his name. It irritates me.”

“Shakespeare is my dog.”

“Shakespeare…to hate him or not to hate him…”

“I’ve always disliked any book that is older than me.”

“I don’t hate Shakespeare. I just don’t understand what he is saying.”

“I absolutely adore the Bard of Avon!”

“He’s a pretty cool guy I guess. His hair is ugly tho. He got MAD CLOUT.”

“OMG I love Shakespeare because of his plots and how it relates to us but that language? Oh no no honey!”

“I like that Shakespeare is Sex, Love, Death. But he has to be extra with his writing.”

“I think reading Shakespeare is like being suffocated with a pillow. I dislike the topics, the vocabulary, and the confusing names—”Mustardseed”? What is that??

“People say Shakespeare is a classic, a legend of the arts, a genius, can never be compared to, he is credited with some of the greatest works of all time, like Biggie.”

“I’ve been told many times that I was going to study Shakespeare. Never have I actually done that. Why? Because whenever it comes to that time, I stop paying attention.”

“Just stop with all of the ‘thou’ and ‘O’ stuff. But I guess it’s just a style, so you keep doing you, man. Shakespeare –> 7/10”

“I feel that people like him because of his name, like identical off-brand shoes to Nike.”

“I’m not a fan of ye olde English because it makes my brain melt out of my ears, but I haven’t read enough Willy to pass an unbiased judgment of him and his work. XOth XOth, Ye Olde Gossip Girl.”

“I’m not in love with him, but I don’t cringe at his name either.”

“When I hear the word ‘Shakespeare,’ I feel like imitating Romeo and killing myself. I also have the burning desire to have Macbeth’s fate (decapitation). I also feel like having the same ending as Julius Caesar: being stabbed thirteen times in the back.”

“Shakespeare and I have a hate-love relationship. I love his work, but the way he writes irks me with a raging passion.”

“So usually when I receive a Shakespeare play to read, I never read it because I feel stupid just trying.”

“Freaked out. Can’t understand. Grade will drop. I do like his stories when I understand them tho.”

“He’s super awesome, he lives up to the hype that surrounds his name. His works are the base of what many other works are written on.”

“Why does everything have to include something sad or love? Why can’t we read about trees or something when it comes to you? Why do I have to think twice as hard to figure out what you’re trying to say? GIVE ME A BREAK, SHAKESPEARE.”

“Meh. He’s chill, not for or against, but he’s for sure overhyped. Meh.”

“You want to know what I think about Shakespeare? You REALLY want to know? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ”

“Raw. Sexual. Ladies’ man. Hat with feather. Poet. Playwright.”

Comments Off on Shakespeare: Let It All Out

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as AP, authors, commentary, Shakespeare