Katherine O’Flaherty Chopin was born on February 8, 1851, in St. Louis, Missouri. The O’Flahertys were a wealthy, Catholic family. Her father founded the Pacific Railroad, but he died when Kate was four. Kate and her siblings were raised by their mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. These women proved to be strong role models. They encouraged Kate’s love of reading and storytelling. Kate was an average student at the convent school she attended. After her graduation, she became one of the belles of fashionable St. Louis society. She met Oscar Chopin, a wealthy cotton factor, married him after knowing him a year, and moved to New Orleans.

Katherine O’Flaherty Chopin was born on February 8, 1851, in St. Louis, Missouri. The O’Flahertys were a wealthy, Catholic family. Her father founded the Pacific Railroad, but he died when Kate was four. Kate and her siblings were raised by their mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. These women proved to be strong role models. They encouraged Kate’s love of reading and storytelling. Kate was an average student at the convent school she attended. After her graduation, she became one of the belles of fashionable St. Louis society. She met Oscar Chopin, a wealthy cotton factor, married him after knowing him a year, and moved to New Orleans.

Oscar Chopin’s circle was the tight-knit French Creole community. Kate led a demanding social and domestic life because of her status. Unusually for the time, her husband was supportive of her independence and intelligence, and her storytelling gifts and her knowledge of French, English, and Creole made her a keen observer of the local culture. She had much to draw from. Her husband’s business gave him prominence in the Creole community, and New Orleans was a city full of diversions, including horse racing, theater, music (Kate was an accomplished pianist herself), and, of course, Mardi Gras.  The Chopins lived in three different houses in New Orleans; this one on Louisiana Avenue was the last. Like many wealthy families, they traveled by boat out of the city to one of the many small Gulf islands to vacation during the summer months. All of these experiences feature in Chopin’s stories and novels.

The Chopins lived in three different houses in New Orleans; this one on Louisiana Avenue was the last. Like many wealthy families, they traveled by boat out of the city to one of the many small Gulf islands to vacation during the summer months. All of these experiences feature in Chopin’s stories and novels.

Oscar’s business failed in 1879. The family moved to their plantation in Natchitoches Parish near the small town of Cloutierville, which strengthened Kate’s connection to the Creole community and gave her more material to draw from. Malaria claimed Oscar’s life in 1880 at the age of 31. Kate moved back to St. Louis with their six children to draw support from her family and place the children in better schools than Cloutierville could provide. The loss of her mother a short time later added to her grief. A family physician suggested writing as an outlet, and Chopin’s literary career was born.

Chopin published her first story in the St. Louis Dispatch. Soon after, her first novel, At Fault, was published privately. Her prolific output over the next fifteen years includes nearly a hundred short stories for adults and children alike. The most famous of these, like “A No-Account Creole,” “Desirée’s Baby,” “The Story of an Hour,” and “A Pair of Silk Stockings” are set in the Creole community and explore its traditions and expectations, especially of the women concerned. Her story collections Bayou Folk and A Night in Acadie were nearly universally praised.

The publication of The Awakening in 1899, however, was a different story. Through its heroine, Edna Pontellier, The Awakening gave Chopin’s themes of independence, art, and possibility free rein. Edna’s decisions go against the expectations for women of the time. A few critics praised the novel’s artistry, but most were very negative, calling the book “morbid,” “unpleasant,” “unhealthy,” “sordid,” “poison.” Novelist Willa Cather labeled it trite and sordid. The overall view was that Edna’s decisions, which modern audiences view quite differently, as scandalous and unfeminine. Chopin was ostracized as a result. Her third story collection was refused by its publisher. The Awakening was removed from libraries for its scandalous content. Chopin herself never got over it; her writing output slowed to the point of cessation. Chopin bought a season ticket to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis and visited on August 20, an unusually hot day. She took to her bed complaining of a severe headache that evening and lapsed into unconsciousness. Two days later, Chopin died, probably from a brain hemorrhage.

In 1969 Norwegian critic Per Seyersted wrote that Kate Chopin “broke new ground in American literature. She was the first woman writer in her country to accept passion as a legitimate subject for serious, outspoken fiction. Revolting against tradition and authority; with a daring which we can hardy fathom today; with an uncompromising honesty and no trace of sensationalism, she undertook to give the unsparing truth about woman’s submerged life. She was something of a pioneer in the amoral treatment of sexuality, of divorce, and of woman’s urge for an existential authenticity. She is in many respects a modern writer, particularly in her awareness of the complexities of truth and the complications of freedom.”

In 1969 Norwegian critic Per Seyersted wrote that Kate Chopin “broke new ground in American literature. She was the first woman writer in her country to accept passion as a legitimate subject for serious, outspoken fiction. Revolting against tradition and authority; with a daring which we can hardy fathom today; with an uncompromising honesty and no trace of sensationalism, she undertook to give the unsparing truth about woman’s submerged life. She was something of a pioneer in the amoral treatment of sexuality, of divorce, and of woman’s urge for an existential authenticity. She is in many respects a modern writer, particularly in her awareness of the complexities of truth and the complications of freedom.”

Chopin did not consider herself a feminist, but her themes of independence and women’s self-realization are stirrings of a movement that would resound throughout the twentieth century. She is now considered one of the essential authors of American literature.

Includes material from the Biography page of the Kate Chopin International Society.

I HAVE two babies; I hope they may never know how warmly at this moment I hate them. I have a husband; we were married because we were very much in love-and him I hate too. I have a large stock of relatives, and them I hate with the heart and should hate with the hand if I had not the misfortune to be well brought up. This emotion of mine, especially in connection with my spouse and offspring, is, up to the present, local and temporary; indeed I think it will not grow into a permanent hatred, but will gradually assume two peculiar forms: toward my children a passionate and slavish devotion, which will make me resent my daughters-in-law; and toward my husband regards, reasonably kind, which will be reciprocated. My feeling toward my relatives, on the other hand, is becoming quite, quite fixed.

I HAVE two babies; I hope they may never know how warmly at this moment I hate them. I have a husband; we were married because we were very much in love-and him I hate too. I have a large stock of relatives, and them I hate with the heart and should hate with the hand if I had not the misfortune to be well brought up. This emotion of mine, especially in connection with my spouse and offspring, is, up to the present, local and temporary; indeed I think it will not grow into a permanent hatred, but will gradually assume two peculiar forms: toward my children a passionate and slavish devotion, which will make me resent my daughters-in-law; and toward my husband regards, reasonably kind, which will be reciprocated. My feeling toward my relatives, on the other hand, is becoming quite, quite fixed.

The truth is, however, that it is not a floor-scrubber and dishwasher that I desire. I could get along with that work or leave it happily undone. It is the care of two children under three that concerns me. It is unremitting and nerve-tearing, and the day in and day out of it is under mining mercilessly my ability to be lovable and to love. Furthermore, I have not the qualifications that would justify entrusting me with sole responsibility for the growth of human beings. Maternal instinct I have in normal amount; I could be trusted to rescue my infants from a burning building, but that is a very different matter from knowing what to do with twenty-four hours’ worth of bodily and mental development every day. I do not want a nursemaid; I have no training for my job, but I have an occasional vagrant idea, and it does not appeal to me to exchange my services to my offspring for those of a hand-maiden with neither training nor ideas. The helper for me should be a trained psychologist, a child-lover, to be sure, but a child-lover with expert knowledge of the needs of growing minds. She should have also training in the treatment of the smaller physical ailments of children. She ought to cost me two thousand dollars a year, but in the present state of women’s wages I have no doubt I could get her for a thousand. And I want her only half the day-five hundred dollars. Our income is sixteen hundred.

The truth is, however, that it is not a floor-scrubber and dishwasher that I desire. I could get along with that work or leave it happily undone. It is the care of two children under three that concerns me. It is unremitting and nerve-tearing, and the day in and day out of it is under mining mercilessly my ability to be lovable and to love. Furthermore, I have not the qualifications that would justify entrusting me with sole responsibility for the growth of human beings. Maternal instinct I have in normal amount; I could be trusted to rescue my infants from a burning building, but that is a very different matter from knowing what to do with twenty-four hours’ worth of bodily and mental development every day. I do not want a nursemaid; I have no training for my job, but I have an occasional vagrant idea, and it does not appeal to me to exchange my services to my offspring for those of a hand-maiden with neither training nor ideas. The helper for me should be a trained psychologist, a child-lover, to be sure, but a child-lover with expert knowledge of the needs of growing minds. She should have also training in the treatment of the smaller physical ailments of children. She ought to cost me two thousand dollars a year, but in the present state of women’s wages I have no doubt I could get her for a thousand. And I want her only half the day-five hundred dollars. Our income is sixteen hundred.

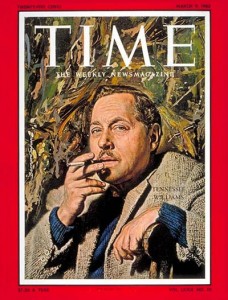

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

Williams famously quipped, “America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” He chose New Orleans as his home, and his work is infused with places and situations that could only have been spawned from the Crescent City’s mix of class, jazz, decadence, and alcohol. He moved into an apartment at 722 Toulouse Street and began working on the plays which would make him famous. The first was a flop. The second, the highly autobiographical The Glass Menagerie, premiered in 1945 to nearly universal acclaim. The character of Amanda Wingfield exerts the same kind of strong influence on her children Tom and Laura that Edwina Williams did on Tennessee, his sister Rose, and their brother Dakin. Fragile, crippled Laura Wingfield is based in no small part on Rose Williams, who possibly suffered from schizophrenia and who was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1943 at their mother’s choice.

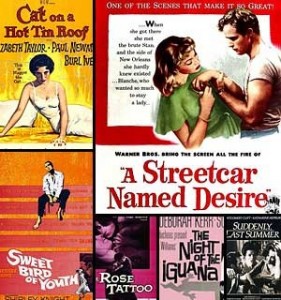

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

Several of Williams’ plays, many featuring clashes of culture and class, were produced and filmed in the years to following. Summer and Smoke and The Rose Tattoo received mixed reviews, but 1955’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (famous for Elizabeth Taylor’s slinking about in a silk slip—and not much else—in an unsuccessful attempt to engage her husband Brick’s, played by Paul Newman, attention), won another Drama Critics Circle Award and a second Pulitzer Prize. Later plays included Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. As Ethan Mordden explains in The Fireside Companion to the Theatre (New York: Fireside, 1988), “His arena is the south, his genre is the cross section of personal relationships, and his archetypes are the somewhat cultured (but inbred and shy) gentlewoman and the brutish male who shatters her flimsy pretenses: in essence, Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski of A Streetcar Named Desire, but, in variation, the Daughter and the Gentleman Caller of The Glass Menagerie, she terminally unsensual and he more breezy than brutish…Almost always, however, Williams deals with the confrontation of the dreamer and realist, his sympathies lying with the dreamer but the victory, in the end, always going to the realist. Thus…the Gentleman Caller does not, as was hoped, stay on to comfort the Daughter…”

There’s a kitchen principle known as “clean as you go” that suggests that if you keep a sink full of hot, soapy water available as you’re cooking, then drop in your messy tools and bowls as you finish using them, the cleanup afterwards goes much faster. The same is true of learning. If you do a little as you go along, there’s much less effort right at the end, whether that means studying for test, writing a paper, or preparing for a seminar. Here are some “learn as you go” principles that will help you be a successful student in AP Lit.

There’s a kitchen principle known as “clean as you go” that suggests that if you keep a sink full of hot, soapy water available as you’re cooking, then drop in your messy tools and bowls as you finish using them, the cleanup afterwards goes much faster. The same is true of learning. If you do a little as you go along, there’s much less effort right at the end, whether that means studying for test, writing a paper, or preparing for a seminar. Here are some “learn as you go” principles that will help you be a successful student in AP Lit.

Oscar Wilde, the Irish playwright who became the darling of British high society, is probably the best-known and most-quoted satirist of the late 19th century. Born in Dublin, Ireland in 1864, Wilde became a well-known lecturer, essayist, and playwright who enjoyed near-universal popularity until the shocking trial that ended his literary career and, not long after, his life.

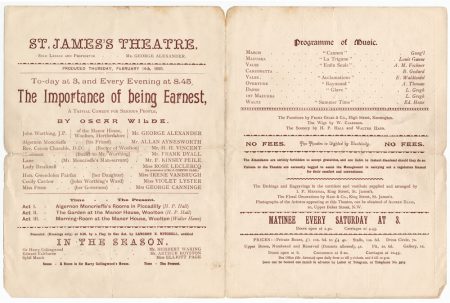

Oscar Wilde, the Irish playwright who became the darling of British high society, is probably the best-known and most-quoted satirist of the late 19th century. Born in Dublin, Ireland in 1864, Wilde became a well-known lecturer, essayist, and playwright who enjoyed near-universal popularity until the shocking trial that ended his literary career and, not long after, his life. The next year, Wilde’s first play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, made its debut to great acclaim. Playwriting became Wilde’s preferred literary style. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed in short order by A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and both An Ideal Husband and his most famous play, The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Each of these works skewered the pretensions of British high society through clever wordplay and Wilde’s satirical wit.

The next year, Wilde’s first play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, made its debut to great acclaim. Playwriting became Wilde’s preferred literary style. Lady Windermere’s Fan was followed in short order by A Woman of No Importance in 1893 and both An Ideal Husband and his most famous play, The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Each of these works skewered the pretensions of British high society through clever wordplay and Wilde’s satirical wit.

Many Faces of Othello

On November 1, 1604, Master of Revels Edmund Tilney notes that a play titled The Moor of Venice was performed at Whitehall Palace for King James I. In the four hundred-plus years since, Othello has become one of the best-known and regarded of Shakespeare’s plays. It has also presented a number of questions regarding its central character, Othello the Moor.

During the Elizabethan era, the word “Moor” could have meant several things. Scholar Ben Arogundade notes that “[‘Moor’] was first used to describe the natives of Mauretania — the region of North Africa which today corresponds to Morocco and Algeria. It was later applied to people of Berber and Arab origin, who conquered and ruled the Iberian Peninsula — the area now known as Spain and Portugal — for nearly eight centuries. From the Middle Ages onwards the Moors were commonly regarded as black Africans, and the word was used alongside the terms ‘negro,’ ‘Ethiopian’ and ‘Blackamoor’ as a racial identifier.

The far more common interpretation, however, is for Othello to be viewed as a sub-Saharan African with black features. It is this portrayal that is most commonly found in modern productions of the play. From Shakespeare’s time until the early 1800s, this meant that the actor tackling the role would have played it in blackface makeup.

It wasn’t until 1826 that Othello was finally played by a black performer: American actor Ira Aldridge. Aldridge emigrated to London at age 17 to pursue his acting career. But his groundbreaking performance wasn’t without criticism. The 1933 performance in Covent Garden was criticized by the paper The Anthenaeum because of the startling new reality of Ellen Tree, the white actress playing Desdemona, being manhandled by Aldridge. And although Aldridge became quite famous in London and abroad, it took nearly a hundred years before another black actor became attached to the role. According to writer Samantha Ellis, “In 1825, the pro-slavery lobby had closed [Aldridge’s] production and the Times‘s critic had written: ‘Owing to the shape of his lips it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English.’ No wonder it took almost a century for another black actor to brave the part.”

Robeson himself enjoyed playing Othello, and it became his signature role for the remainder of his career. As Ellis notes, “For Robeson, it was more than just a part: it was, as he once said, ‘killing two birds with one stone. I’m acting and I’m talking for the negroes in the way only Shakespeare can.'”

But as well-received as the production was by the Oscar crowd, its release during the height of the Civil Rights Movement dampened its reception with audiences. Arongundade remarks that “…[Olivier’s] blackface portrayal troubled American critics when the film opened there in 1966…sensitivities about black identity were at their height, and many saw Olivier’s chosen aesthetic as outdated.”

Modern theater companies wishing to explore the themes of Othello in new ways have explored variant casting. A 1997 production of the play in Baltimore starred Patrick Stewart as Othello, the lone white actor in a racially-flipped cast in which every other actor was African-American. Stewart, pictured here with Patrice Johnson as Desdemona, explained, “One of my hopes for this production is that it will continue to say what a conventional production of Othello would say about racism and prejudice… To replace the black outsider with a white man in a black society will, I hope, encourage a much broader view of the fundamentals of racism.” A review in the Baltimore Sun said, “It is a tribute to the concept as well as Stewart’s performance that the initial awkwardness falls away as early as his second scene…Stewart, who possesses a calm assuredness at the start of the play, lets the theater’s predominantly white audience experience how completely foreign Othello must have felt in a society where he was viewed as the outsider.”

Sources:

Ben Arungodade, “What Was Othello’s Race?” and “The 18 Most Memorable Othello Actors Performances”

Baltimore Sun review of Sir Patrick Stewart Othello

Jerry Brotton, “Is This the Real Model for Othello?”

Samantha Ellis, “Paul Robeson in Othello, Savoy Theatre, 1930”

Emily Anne Gibson, “The Face of Othello”

Andrew Haydon, “Othello – Deutsches Theatre”

Othello Relating His Adventures to Desdemona by Carl Ludwig Friedrich Becker, 1880.

Comments Off on Many Faces of Othello

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as AP, background, commentary, drama, Othello, plays, Shakespeare