Survival stories have been a popular mainstay of literature stemming back to the oral tradition. The British and American branches of literature are full of them.  Daniel Defoe’s 1719 tale Robinson Crusoe exemplifies many of the hallmarks of these tales we find familiar: a stranded hero, a deserted island, meetings and clashes with various native cultures, and eventual rescue, where the hero returns home a changed man for his experience. The book’s popularity spawned an entire subgenre of literature called Robinsonade, all of which contain a stranded hero, a new beginning, encounters with natives, and commentary on society. These influences can be seen in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a particularly biting piece of satire that uses the castaway motif to savage various aspects of English society, and the modern film Cast Away (2000),

Daniel Defoe’s 1719 tale Robinson Crusoe exemplifies many of the hallmarks of these tales we find familiar: a stranded hero, a deserted island, meetings and clashes with various native cultures, and eventual rescue, where the hero returns home a changed man for his experience. The book’s popularity spawned an entire subgenre of literature called Robinsonade, all of which contain a stranded hero, a new beginning, encounters with natives, and commentary on society. These influences can be seen in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a particularly biting piece of satire that uses the castaway motif to savage various aspects of English society, and the modern film Cast Away (2000),  in which Tom Hanks plays a stranded Federal Express executive who survives alone on an island in the South Pacific for four years with the help of the contents of FedEx packages that washed up on the island with him, including a personified volleyball named Wilson.

in which Tom Hanks plays a stranded Federal Express executive who survives alone on an island in the South Pacific for four years with the help of the contents of FedEx packages that washed up on the island with him, including a personified volleyball named Wilson.

In the Victorian era, one book of Robinsonade rose above all others in popularity, The Coral Island, published in 1858 by the Scottish author R. M. Ballantyne. The Amazon summary for this book reads, “When the three sailor lads, Ralph, Jack and Peterkin are cast ashore after the storm, their first task is to find out whether the island is inhabited. Their next task is to find a way of staying alive. They go hunting and learn to fish, explore underwater caves and build boats – but then their island paradise is rudely disturbed by the arrival of pirates.”

Clearly, Golding is in familiar territory, which is unsurprising. The Coral Island, one of the first adventure books written for boys and employing a boy as the central character, became wildly popular in Great Britain. The Coral Island has been required reading for British schoolchildren since the Victorian era (Golding will most certainly have read it in school), and the characters of Lord of the Flies reference it in Chapter 3 when Jack, Ralph, and Simon return from their fact-finding mission and confirm they have all been stranded.

Part of The Coral Island‘s popularity was its clear messages about morality and choices. Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin of the story are tested by their isolation, their encounters with pirates, and their interactions with the cannibalistic inhabitants of nearby islands. Through a series of adventures, the boys’ friendship and loyalty are tested and proved, and at the end the three friends, older and wiser, sail back to England together. Ballantyne included them in a sequel, The Gorilla Hunters, in 1861.

Part of The Coral Island‘s popularity was its clear messages about morality and choices. Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin of the story are tested by their isolation, their encounters with pirates, and their interactions with the cannibalistic inhabitants of nearby islands. Through a series of adventures, the boys’ friendship and loyalty are tested and proved, and at the end the three friends, older and wiser, sail back to England together. Ballantyne included them in a sequel, The Gorilla Hunters, in 1861.

Victorian audiences ate it up. In a time when virtue was valued above all else, the purifying adventures of the novel revealed English boyhood at its very best, a trait embodied in Jack’s confident assertion in Lord of the Flies that their group would survive triumphant simply because they were English and therefore the best at everything. However, the book also contains the Victorian fault of viewing its English central characters as superior in breeding and morality to the “savage” native inhabitants of the region, who are dismissed as evil or praised as good based on whether those people have submitted to English values or have adopted Christianity. Golding, as you will see, explores these moral ideas with his characters in quite a different way.

A clear and rather extensive analysis of the literary influences and history of The Coral Island may be found at its Wikipedia entry. And since Golding clearly borrowed many elements of The Coral Island for Lord of the Flies, perhaps that helps us get close to solving one of the little, yet provocative, mysteries of the book: What is Piggy’s real name? (Hint: Who are the three main characters in The Coral Island?)

Christopher King, the art director for the American publishing house Melville House, explored some of the design choices for Lord of the Flies in

Christopher King, the art director for the American publishing house Melville House, explored some of the design choices for Lord of the Flies in

In the end, the judges unanimously selected the mixed media work of 15-year-old Sarah Baxter as the contest winner. An interview with Sarah was published in

In the end, the judges unanimously selected the mixed media work of 15-year-old Sarah Baxter as the contest winner. An interview with Sarah was published in

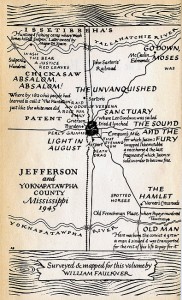

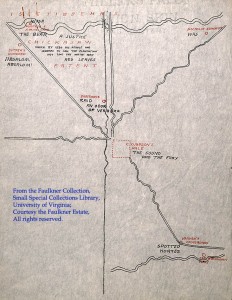

Much like English novelist Thomas Hardy, whose “Wessex” is a fictional amalgam of real locations, Faulkner based Yoknapatawpha County on very real places. Faulkner lived for most of his life in Oxford, Mississippi. In Faulkner’s work, Oxford becomes the town of Jefferson, while the real Jefferson County is named “Yoknapatawpha” after the old Chickasaw word for the Yocona River south of town. The county is located in north central Mississippi not far from the Tennessee border. This 1947 map indicates the primary locations of several of Faulkner’s major works, including not only Light in August but also his masterworks Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury.

Much like English novelist Thomas Hardy, whose “Wessex” is a fictional amalgam of real locations, Faulkner based Yoknapatawpha County on very real places. Faulkner lived for most of his life in Oxford, Mississippi. In Faulkner’s work, Oxford becomes the town of Jefferson, while the real Jefferson County is named “Yoknapatawpha” after the old Chickasaw word for the Yocona River south of town. The county is located in north central Mississippi not far from the Tennessee border. This 1947 map indicates the primary locations of several of Faulkner’s major works, including not only Light in August but also his masterworks Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury.

Lord of the Flies Analysis

“Like any orthodox moralist Golding insists that Man is

a fallen creature, but he refuses to hypostatize Evil or

to locate it in a dimension of its own.

On the contrary Beelzebub, Lord of the Flies,

is Roger and Jack and you and I,

ready to declare himself as soon as we permit him to.”

—from “The Fables of William Golding” by John Peter, 1957

—E. M. Forster, introduction to Howard-McCann edition of

Lord of the Flies, 1962

—from The Novels of William Golding by S. J. Boyd, 1988

Golding himself had this to say about Lord of the Flies in his essay collection A Moving Target (1985):

More than a quarter of a century ago I sat on one side of the fireplace and my wife on the other. We had just put the children to bed after reading to the elder some adventure story or another—Coral Island, Treasure Island, Pirate Island, Magic Island. God knows what island. Islands have always and for good reason bulked large in the British consciousness. But I was tired of these islands with their paper-cutout goodies and baddies and everything for the best in the best of all possible worlds. I said to my wife, “Wouldn’t it be a good idea if I wrote a story about boys on an island and let them behave the way they really would?” She replied at once, “That’s a first class idea. You write it.” So I sat down and wrote it.

Yet there is something more. In a way the book was to be and did become a distillation from that life. Before the Second World War my generation did on the whole have a liberal and naïve belief in the perfectibility of man. In the war we became if not physically hardened at least morally and inevitably coarsened. After it we saw, little by little, what man could do to man, what the Animal could to do his own species. The years of my life that went into the book were not years of thinking but years of feeling, years of wordless brooding that brought me not so much to an opinion as a stance. It was like lamenting the lost childhood of the world. The theme defeats structuralism for it is an emotion.

The theme of Lord of the Flies is

grief, sheer grief, grief, grief, grief.

Comments Off on Lord of the Flies Analysis

Filed under AP Literature

Tagged as analysis, AP, books, commentary, LOTF